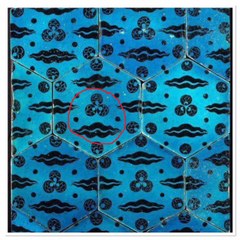

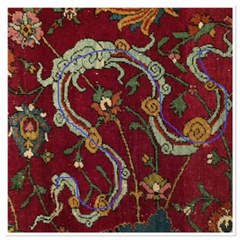

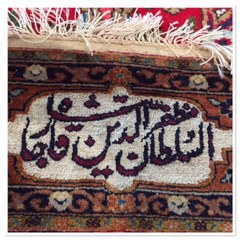

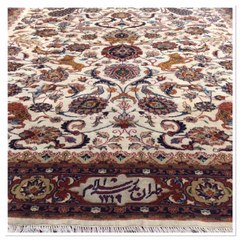

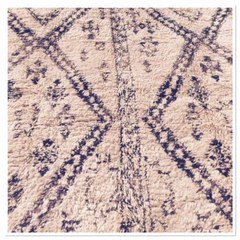

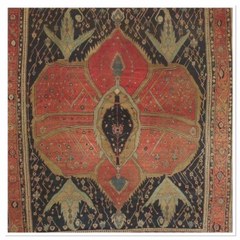

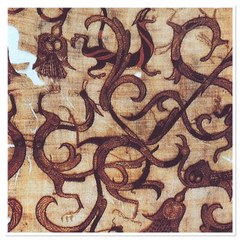

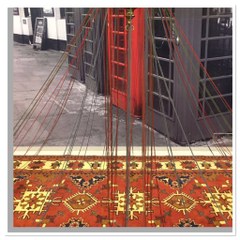

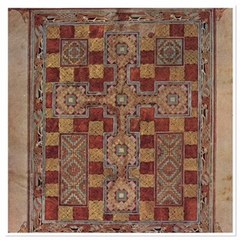

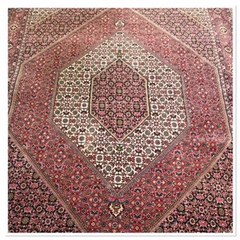

Recently my attention was drawn back to the origin of Cintamani by a fellow carpet enthusiast, Mr Andrew Hauton, in a Facebook Group called "The Weftkickers”. The Cintamani design in Persian carpets is three circles arranged in a triangle generally on top or underneath one or two wavy “line(s)” called the cloud band. It has been the subject of speculation ever since it’s’ existence came to attention in the carpet world and its origins and meaning remains speculative. In my previous article I touched on the subject of Cintamani and its relationship to the Sirius star, but I did not study the Sirius star from the view of Ancient Persian cosmology and I am glad to see the connection between the Cintamani, the Cloud band and the Arrow and bow, which is related to the name of the Sirius star in Persian, being Tir (also translated to Arrow).

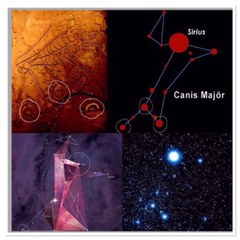

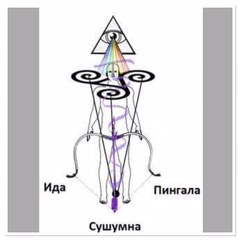

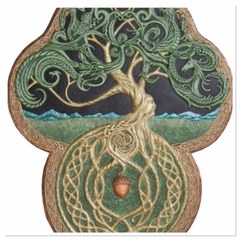

Sirius has played a major role in the Ancient World in relation to severe weather, with the Ancient Egyptians viewing it as the reason for the annual flooding of the Nile and the Ancient Greeks viewing it as the reason for harsh and hot summers. Even in China and India Sirius was the maker or breaker of a good harvest season. For the Ancient Persians Sirius, the brightest star in the sky, was known as Tir. Tir is also the fourth month in the Iranian calendar and it was connected to the rainfall season in July. So important was this star that the Zoroastrians had an entire festival in honour of appeasing Sirius/Tir into giving good rainfall, and all participants even wore a rainbow band around their wrists. ‘We sacrifice unto the rains of Tishtrya. We sacrifice unto the first star; we sacrifice unto the rains of the first star, whose eye-sight is sound.’ - Tishtar Yasht (Zoroastrian Hymn to the Star Sirius). In Ancient Persian mythology Tistrya (Tir) fights against Apaoso for the possession and liberation of the waters contained in the (cosmic) ocean Vourukaṧa. Tistrya is often depicted as an arrow also being shot to release the “waters of life” and thus fertilizing the goddess who will in turn birth good harvests.

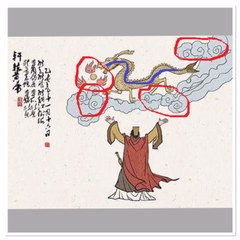

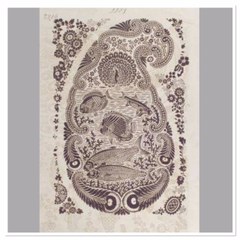

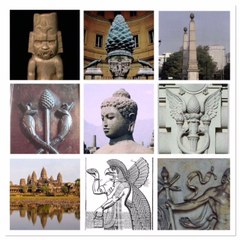

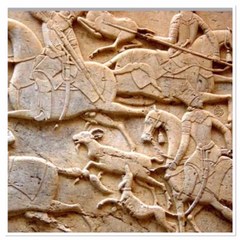

The Persians were not the first to link Sirius to the form of an arrow. All other civilizations did the same with some depicting Sirius as the entire bow and arrow, others depicting it as the arrow and others depicting it as the tip of the arrow. Wanting to the influence the weather is nothing new with scientists even today attempting to seed clouds to influence the particular precipitation that is desired in certain areas, either by creating more moist or dispersing moist. Cloud seeding is the process of releasing chemicals into the clouds to alter its behaviour and it was recently found that something as simple as table salt can do just that. The ancients tried everything from ritual sacrifces to dances (in zig zag formation representing water and lightening) to playing harps and flutes, believing that the frequencies could influence weather patterns. They even shot arrows into the clouds to “bring rains”. The cloud band in the Cintamani design is very similar to the shape of ancient bows and the Cintamani itself in its triangular arrangement is very similar to an arrow tip.

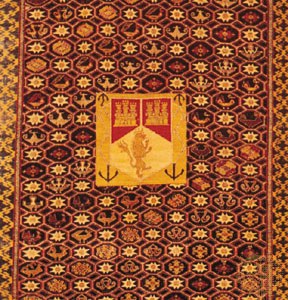

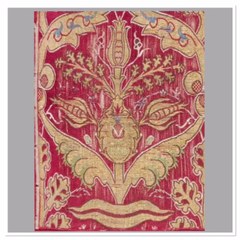

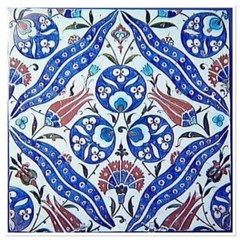

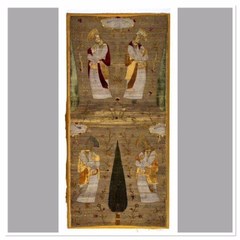

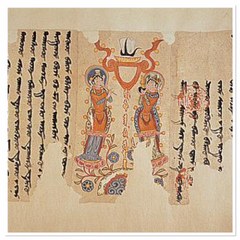

The Cintamani design can be found all around the globe in all arts of all civilizaitons from the pagans’ “mother goddess” (generally depicted as a trinity) to the holy trinity in many of the modern day religions. To find it in a Persian carpet, however, woven by Turkic tribes and placed on top/underneath wavy lines, definitely requires more investigation, for nothing in Persian carpet designs are accidental. Considering the Turkic tribes converted to Islam it would be a good start to look at practices of ancient Arabic religions. In Arabic paganism and other semitic tribes around Mecca, the main deity that relates to this subject was the goddess, Al-shi’raa. She was the Meccan goddess of the star Sirius who had a popular cult among the pagan Arabs who lived in and around pre-Islamic Mecca in the Hijaz: the goddess was venerated chiefly by the tribes of Banu Khuza'a and Banu Qays. The cult of al-Shi'ra was so prominent among the tribes of pre-Islamic Mecca that it was specifically highlighted and condemned in the Qur'an. As one of the brightest stars in the sky, al-Shi'ra was thought to grant wealth and good fortune to her worshipers and oaths were often sworn in her name; another of which was Mirzam al-Jawza' and was believed to be the 'Doorkeeper of Heaven'. The worship of stars (najm) and other celestial objects (kawkab) was a common religious practice among the pre-Islamic Arabs and other Semitic peoples; especially among the nomadic Bedouin who grazed their flocks at night and observed the stars for directions. The temples of the sedentary Arab tribes who dwelt in the towns, most notably the Ka'aba of Mecca, were designed by certain.corners facing certain stars: a common Semitic religious feature including temples having rooftops from where stars and planets could be worshiped and observed.

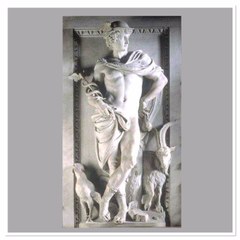

Quzah wass the Meccan god of storms, thunder and the clouds who was worshiped by the tribes of Banu Khuza'a and Banu Quraysh at his shrine in the vicinity of al-Muzdalifah, located not far from Mecca. Quzah was, in Meccan mythology, portrayed as a giant archer who lived in the clouds and fired hailstones at the shayatin (demonic spirits) from his bow: the crashing of thunder, said to be the battle-cry of the god, was believed to scare away spirits of disease and misfortune. The rainbow that appeared after a rainstorm was considered by the polytheists of Mecca to be a ladder to the heavens and Quzah was its guardian. In the northern regions of the Arabian peninsula, Quzah was often the consort or husband of Manat, goddess of destiny. The cult of Quzah in the Hijaz may have originated among the cousins of the Arabs; the Edomite tribes of southern Jordan, whose chief deity was a sky god called Qos in their language. The belief in Qos continued through with the Nabataeans who represented him a king flanked by bulls, holding a multi-pronged thunderbolt in his left hand. The memory of the god is still retained in modern Arabic with the words qaws' Quzah meaning ''Bow of Quzah'', a metaphor for a rainbow. The 'ifada was a feast in pre-Islamic times which was held by the polytheists of the tribe of Banu Quraysh at Muzdalifah in veneration of Quzah as part of their tahannuth (devotional religious practices) and istisqa (rain-making rituals), during the hallowed month of Ramadan. Amazingly in Quran it is mentioned Ghausain meaning two bows or two cloud bands associated with Sirius the three stars: “it is He Who is the Lord of Sirius”, (Qur'an, 53: 49) and “He was two bow-lengths away or even closer”. (Qur'an, 53:9)

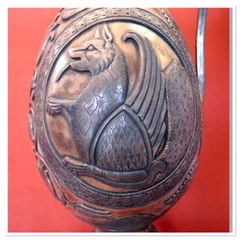

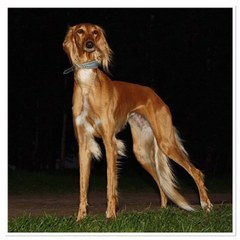

According to the old Turkish clans, this star was a sacred gate that joined the Earth with the heavens, the luminous realm of the gods. The star was the frontier between the spirit realm and the material realm where mortals reside. You could also call it the line that separates gods from humans. The gods would send favors to people from this gate, and shamans would fly to the gate and communicate with the gods, but they were unable to truly reach the star and pass through to the other side. The gods would send a messenger from their realm and listen to what mortals had to say through this messenger. The symbol of the celestial (blue) wolf that descended from the sky in a blue beam of light is pretty common to the creational myths of the Turks. Sirius is known from Ancient times as the Dog star and part of the Canis Major constellation. In one of the Göktürk (the celestial/blue Turks) myths, a child whose entire family was killed (symbolizing the solar system) survives with the guidance of a she-wolf (the Dog Star). The wolf suckles the child and proceeds to marry him, and the Sky God descends to Earth in the form of a wolf. According to other esoteric teachings, the creation of the planet Earth was in fact the result of a union between our solar system and Sirius (the Dog Star). The similarities between these teachings and the tale of the wolf that married an orphaned child are intriguing.

Wolves were considered sacred in old Turkic beliefs. The symbol of the she-wolf has important significance in most creational myths and the collected symbolism of the world. The myth of a she-wolf called Ashina, who was sent to Earth from the heavens, has survived to this day. Many Turkic clans have used wolves in their flags, and their commanders were called Kök-Böri. The word kök is an old form of the modern word gök,which means sky, and böri is the word for wolf. You can find wolf reliefs in the earliest known historical expression of the First Turkish Empire, the Bugut Monument that was commissioned by Mahan Tigin (Prince Mahan). How meaningful is it that a wolf figure appeared on the first printed banknote of Atatürk’s government? His friends nicknamed him “crazy Turk” after the banknote incident. There are various opinions about the color of the star as well. Although Sirius is widely thought to be a red/orange color, both Manilius, a first century poet, and Avienus, an author from the fourth century, describe the star’s color as light teal. The star is also named the Blue Star in Japanese.

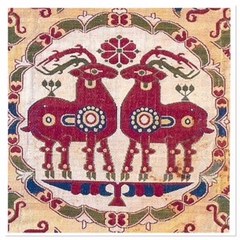

The Dogon tribe in Africa is well-known for their ancient knowledge on the star, Sirius. They believe that the gods came from Sirius and imparted on them knowledge of the star system that has only recently been confirmed in science as correct. According to the Dogon Sirius is three stars: Sirius A which is the big white giant star, Sirius B which is a smaller and less bright star (although one of the heaviest objects in our solar system) and “Sirius C” (which we have been unable to detect yet as it is a very dark star, but astronomers believe it is also orbiting the other two by observing anomalies in the orbiting behaviour of the other two stars). Sirius as a three star system could thus be represented by the three circles of the Cintamani.

Correlating all this information, Sirius was seen as the power behind fertility on Earth and studying Persian carpet symbolism, could open up more direction into ancient cosmology and astronomy and astrology. Thus the Cintamani design could very well be the most potent sign of fertility in Persian carpets and art. For the newly converted Turkic tribes (who were in love with Persian art) to include this design in their carpet weaving is no surprise, considering the Shamanic background and the importance of symbols of fertility and protection in their daily lives.

Sources:

· http://www.green-man-of-cercles.org/articles/from_roman_to_romanesque.pdf

· Point of Origin: Gobekli Tepe and the Spiritual Matrix for the World’s ...By Laird Scranton

· Sirius Matters, p 29 By Noah Brosch

· http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/tistrya-2

· https://iranian.com/main/blog/nabarz/star-sirius-tishtrya-tir-sothis.html

· http://www.iranreview.org/content/Documents/_Arash_the_Archer_and_the_Festival_of_Rain.htm

· http://www.thehiddenrecords.com/davinci_part2.htm

· https://vigilantcitizen.com/hidden-knowledge/connection-between-sirius-and-human-history/

· http://www.crystalinks.com/sirius.html

· https://newearth.media/dagdas-haarp-musical-weather-modification/

· https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sirius

· http://www.harrypotterforseekers.com/articles/siriusforseekers.php

· https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cloud_seeding

· http://www.thewisemag.com/mystery/sirius-the-mysterious-star-of-the-goddess-isis/