Medicinal

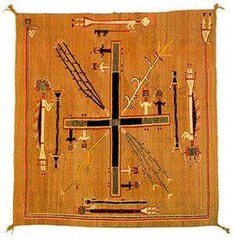

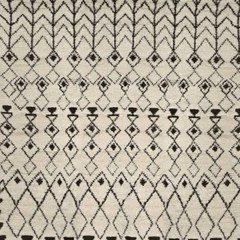

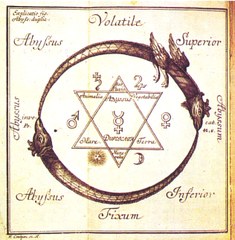

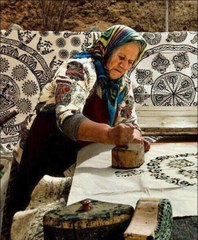

When the mummified tattooed Iceman, Otzi, was found in the Alps, it became clear that the practice of tattooing was far older than once thought. It was estimated that Otzi lived between 3400 and 3100 BCE, a much earlier date than the other tattooed mummies found in Egypt. Ötzi had a total of 61 tattoos consisting of 19 groups of black lines. These include groups of parallel lines running along the longitudinal axis of his body and to both sides of the lumbar spine, as well as a cruciform mark behind the right knee and on the right ankle, and parallel lines around the left wrist. The greatest concentration of markings is found on his legs, which together exhibit 12 groups of lines. Radiological examination of Ötzi's bones showed "age-conditioned or strain-induced degeneration" corresponding to many tattooed areas, including osteochondrosis and slight spondylosis in the lumbar spine and wear-and-tear degeneration in the knee and especially in the ankle joints. It has been speculated that these tattoos may have been related to pain relief treatments similar to acupressure or acupuncture. There are some other "younger" mummies found sporting geometrical tattoos made from plant based dyes/inks, that researchers believe had medicinal qualities as these tattoos were placed on acupuncture points as well, further strengthening the case of medicinal tattoos. The ancient cultures not only tattooed themselves with healing symbols but also carried it on their person either as talismans, on their garments and even carpets. The Navajo healing carpets are a great example of this where the shaman makes a sand carpet with healing symbols believing that each of these symbols are living beings, who will assist the ailed person to regain harmony and balance in their bodies and ultimately heal.

Identification and status

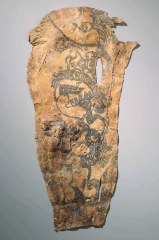

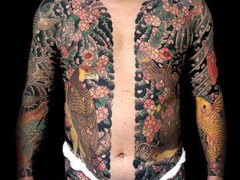

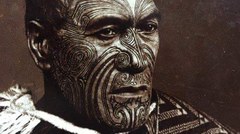

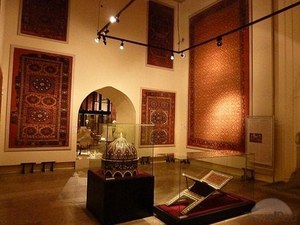

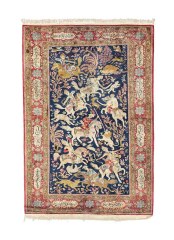

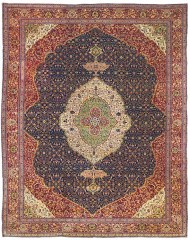

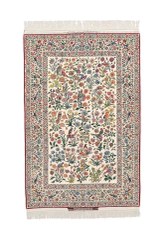

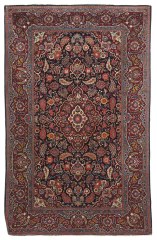

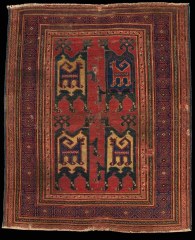

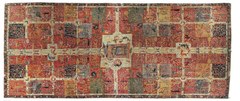

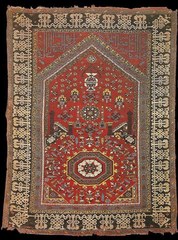

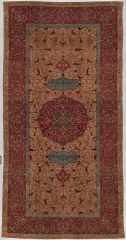

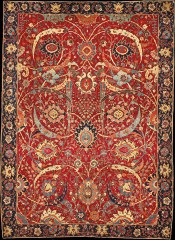

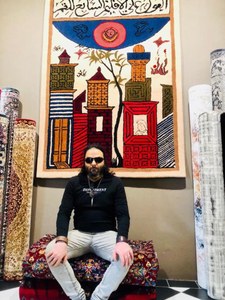

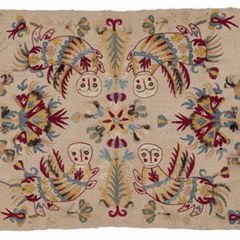

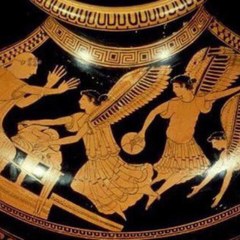

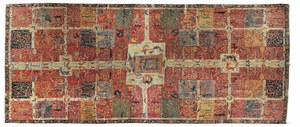

Ancient tattoos (called khalkubi in Persian) also indicated the bearers identity or status in society. A beautiful example of this were the Scythians. From 700 - 200 BC the Scythians in the Altai Mountain region were a powerful warrior society known for their tattooed mummies and glorious art forms. The oldest surviving carpet, the Pazyryk, was found in the grave of a Scythian prince and depicts horses, stags and griffins, all of which are prominent in all their art forms. On their mummies glorious tattoos of stags, horses and goats can be found as well as birds of prey (representing heaven), herbivores (representing earth) and feline hunters such as leopards and lions (representing the afterlife/underworld). These symbols were also beautifully woven onto their garments, their weaponry masterfully crafted with it and many exquisite golden statues with these animals were made. The women were also warriors and due to their fierceness gave birth to the "Amazon" legends. In this civilization the tattoos they carried indicated their status in society (i.e. royalty, warriors and also rights of passage) and also their shaman culture. They were not just warriors but great traders and merchants and through their dealings with surrounding kingdoms, it is believed that their tattoo culture caught on and soon many other cultures sported tattoos as well. In the Roman Empire, however, tattoos were only used to identify criminals or slaves, for everyone else it was strictly forbidden, yet the early Christians tattooed themselves with a small cross on their wrist to identify each other. This tattoo could easily be concealed from the Romans who were persecuting them and it was imperative in knowing who could be trusted in this "secret society". This practice was later outlawed by Constantinople, after he converted to Christianity, citing as his justification Leviticus 19:28, which says,”You shall not make any cuttings in your flesh for the dead, nor tattoo any marks on you: I am the Lord.” During the Crusades, however, the knights had the Cross of Jerusalem tattooed on them so that they could be identified and buried as Christians in the event of their death. They also had this cross woven in their flags and garments. The Japanese were another culture who had a ban against tattoos and only used it to identify criminals. The peasants rebelled against this due to the fact that only the royals and elite could wear colourful kimonos with elaborate designs. They secretly got body suit tattoos depicting popular Japanese paintings that they could hide under their plain clothing. Even today visible tattoos are not widely accepted in Japan but the infamous Yakuza still have their entire bodies tattood by tattoo masters. The Ainu culture in Japan (believed to be Iranian peoples) used to tattoo the mouths of women as a right of passage. In fact, a woman could only get married if she had her mouth tattooed. They also made beautiful garments, tapestries and kilims. In the Polynesian Islands the warriors had elaborate facial tattoos, each unique to the wearer and also near full body suit tattoos with different geometric designs and lines. Not only did it identify the specific tribe and their status in it, but it also indicated the strength and power of the person who could endure the pain of receiving these tattoos. After the Europeans came in contact with these tribes the tattoo culture caught on in Europe and the royals and elite started getting tattoos of their family crests. They too had these crests woven in flags, tapestries and clothing. In the handmade carpet culture each tribe's carpets can also be identified by the symbols and colours that they use. Some cities use only certain colours in their carpets, such as weaving centers in Nain. Some carpets are signed by the designer or weaver that serves as identification.

Protection, fertility and blessings

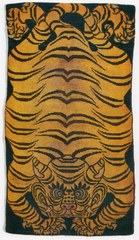

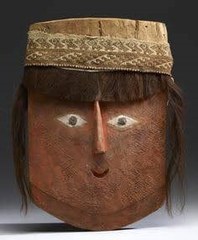

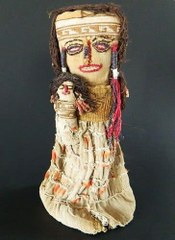

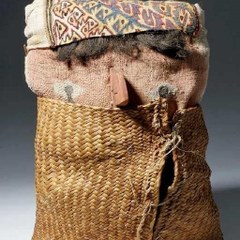

Ancient tattoo cultures believed that they embody the powers of the symbols that they tattooed on their bodies and that is till true in the Japanese culture of bodysuits. Ancient Egyptian female mummies have been found with tattooed symbols of fertility on their abdomens and on their thighs. The Scythian warriors often had tattoos of birds of prey, stags and griffons that empowered them in battle. The Celts (Scythians who migrated West) carried on this tradition of protective and fertility tattooes. In 50 BC, the infamous Julius Caesar wrote, “All Britons paint themselves with woad, which turns the skin a bluish-green colour, hence their appearance is all the more horrific in battle.” These cultures also crafted items of protection on their weaponry, in the form of talismans, on their garments and also their carpets. The Celtic knot was widely used in all Celtic art forms. This tradition is still carried on in tribal handwoven carpets with symbols such as the scorpion that denotes protection, fertility and blessings. The ram horn and snake symbols both denote rebirth, for the sheep's ability to continuously create new wool and the serpent's ability to shed it's old skin. The serpent was also a sign of healing since it's poison was often used in medicine. In Tibetan monestries tiger carpets were and are widely used since tiger skin in Tantric Buddhism represents the transformation of anger into wisdom and insight, and is thought to protect the meditator from outside harm or spiritual interference. Tibetan tantric rugs are the seats of power employed by practitioners of Esoteric Buddhism. These rugs typically depicted the flayed skin of an animal or human and, together with associated ritual utensils, are the tools employed in the enactment of Esoteric rites associated with protective deities. The employment of these images and ritual tools celebrate the power of detachment from the corporal body that advanced Buddhist practitioners strive to attain. In some cultures facial tattoos were applied to disguise gravely ill people so that the Angel of Death could not find them. This was also believed to alter their life path. In a similar fashion in Judaism when a person falls gravely ill their name is changed so as to change their vibration and life path. We believe that woven carpets played a similar role. Based on the symbols and colours present in the carpet and the space it was placed, it would alter the presiding energy of the space and alter the course of the individual.

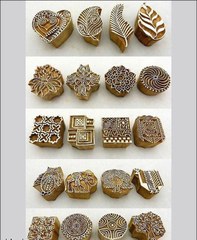

Investigating the tattoo cultures, it becomes clear that many of them originated in the Iranian plateau and all of them had a weaving culture as well. Could the tattoo artists and weaving designers have been the same people? We think so. Was the tattoo culture born from the weaving culture? We think so. Were both tattoo and weaving cultures born from shamanism and rituals? We say a resounding "YES"! Carpets were not just woven to protect against the elements, just like tattoos were not just done for protection. They were status symbols, luxurious and lush, and both of them required (and require) tremendous skill and a lot of time to perfect! The creators of these art forms no doubt had to have extensive knowledge of cultural symbolism, shamanism, craftsmanship, herbalism, biology, medicine, art and much more! Shervin Ghorbany firmly believes that, based on this, the theory that carpets were woven out of necessity and later changed to luxury items, is entirely incorrect. He believes that it was woven for decorative and spiritual purposes, that later changed to protection against the elements out of necessity. Just as the art of tattooing has survived and continues, so too does the art of weaving carpets. Neither can be rushed and both requires attention to detail, perseverance and a love and knowledge of art and symbolism.