The Silk Road brings visions of mysterious and exotic merchants and travellers from distant lands carrying extraordinary goods on the backs of camels. It was called the Silk Road because the silks of China became the most important commodity for all the trading partners and became the form of payment, however, at a later stage the Sasanid coins became the accepted form of payment. This long winding road has been the source of many fantastical stories and adventures of people from all over the world. To write its’ colourful history would probably take as long as it did to develop this road, but I will do my best to summarize all the influences that melted together to give us such a great memory. Three main players started this incredible road that would eventually connect cultures for centuries to come before the Internet was even a thought.

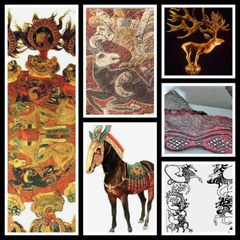

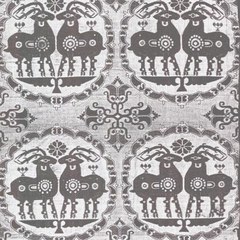

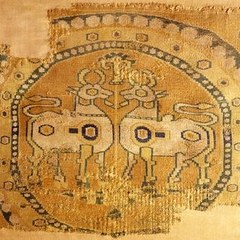

We start our journey in the region of the Hungarian plains stretching all the way to the Chinese Kansu corridor (8BC to around 600AD) where the highly skilled Scythian warrior tribes lived. One look at the arts and crafts they left behind and it is clear that not only were they extraordinary warriors but they had excellent taste in décor and design! Before melting into various different tribes including the Sogdians, they carved out a road that connected many villages and in so doing they encouraged trade along it. Chinese silks were found in a Scythian burial in Germany dated to 6th BC indicating that the Scythians traded with the Chinese from very early on.

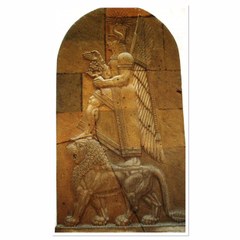

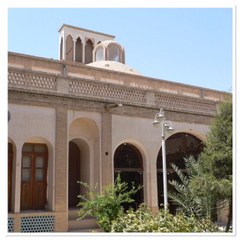

Down South the mighty Achaemenid Empire ruled by Cyrus the Great carved out their own path. The Royal Road stretched 2,857km from Susa to the Port of Smyrna (modern day Izmir) that allowed royal couriers to carry messages the entire distance in only 9 days. This was achieved by having postal stations (the first in the world) and relays at regular intervals where there awaited fresh horses and couriers to continue the journey. The road was maintained and protected by the king. When Alexander the Great took over the Persian Empire he travelled further east and establish his city, Alexandria Eschate, in today’s Xinjiang province of China. His successors went further into Sogdiana and even as far as Kashgar in Chinese Turkestan which led to the first contact between the Chinese and their neighbour. The Royal Road was extended to include these new areas.

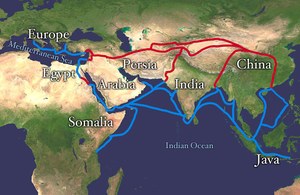

At the same time the Chinese Emperor Wu also got his own road after he took it from his enemies, the Hsiung-nu, and hearing about the riches of neighbours outside the borders of China (Ferghana, Bactria and Parthia), his desire to connect his road to their lands became of utmost importance. At this point China already had a “Maritime Silk Road” that connected it to India.Trade between these three commenced and thrived until another very wealthy customer entered the fray. When the Romans annexed Egypt and saw the incredible objects of beauty on offer, a love affair started and I am not just referring to Julius and Cleopatra. The Romans realized just how much more trade along the Silk Road could enrich Rome and once the Roman ladies held silk in their hands, the days of cotton and wool garments were gone! As much as the Roman Senate tried to prohibit them from wearing these see-through silk garments and stop them from sending all their money east, it simply didn’t work! Unfortunately the wealthy Rome fell on hard times around the 5th Century and with it the high demand for Asian products.

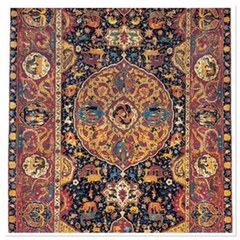

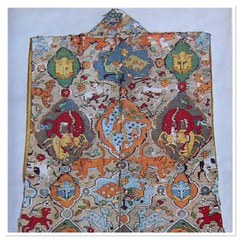

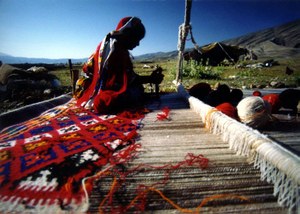

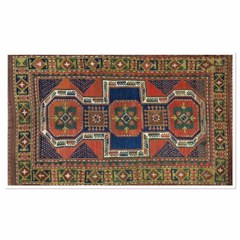

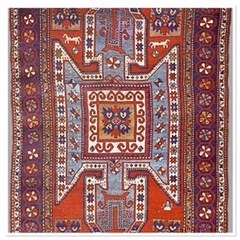

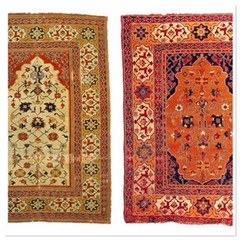

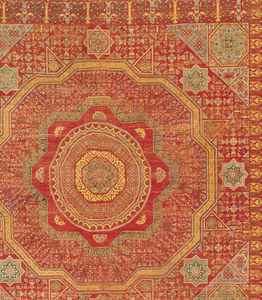

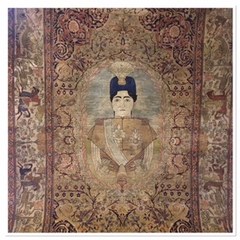

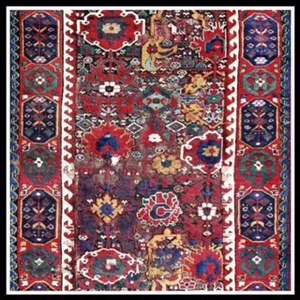

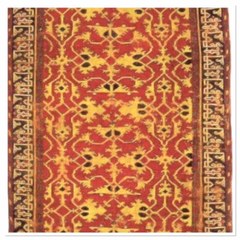

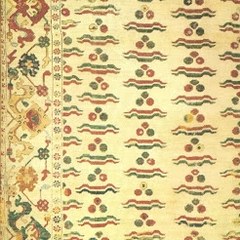

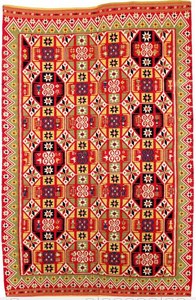

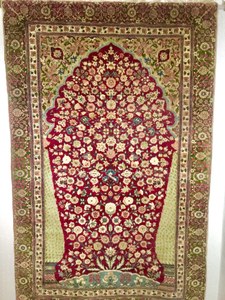

With all the inflow of Western money the Sasanid, Sogdian and Chinese Empires flourished and there was no end to the exquisite products they produced. With the acquisition of silks from China the Sasanids and Sogdians were able to make textiles that are still renowned today and the finest, most unbelievable Persian carpet creations known to man.

The Byzantine’s didn’t enjoy very friendly relations with the Sasanids but as the successor of the Eastern Roman Empire its citizens came to rely on the products from the East. The Sasanids controlled its entrance to the Silk Road and didn’t play nice with the threatening Byzantine forces. The Sogdians, being cunning and very diplomatic, cut a deal with the Byzantines to bypass the Sasanids and trade directly with them instead. Even though some Byzantine monks secretly stole some silkworm eggs at one point that gave the Byzantine Empire the monopoly on silk production in Europe, the Chinese silks were still seen as far superior quality and the Byzantines thus continued their trade with the Sogdians.

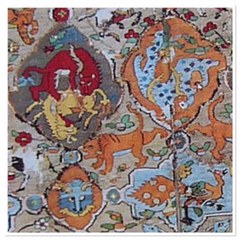

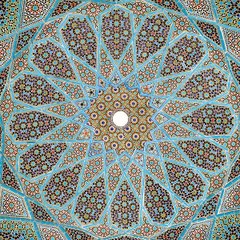

Rising forces of Islam saw many changes in the mighty world empires at the time and Persia would finally fall into its hands. This saw a massive creative transformation in the arts and Islamic art became the new craze all over, but it also placed a large part of the Silk Road in their hands. At the same time the Tang Dynasty in China managed to finally defeat the ever protruding Tibetan forces, a move that ensured the permanent reopening of the Silk Road in China. This was the start of the Golden Era of the Silk Road as the most important trade route from East to West. The mix of foreign cultures, religions, arts, crafts, wisdom, knowledge, information all made humankind so much richer. The Tang Dynasty also increased their Maritime Silk Road travelling not just to India, but also the Persian Gulf, the Red Sea, into Persia, Mesopotamia (sailing up the Euphrates River in modern-day Iraq), Arabia, Egypt, Aksum (Ethiopia), and Somalia in the Horn of Africa.

As much as the Silk Road contributed to the wealth and well-being of all involved, it also contributed to the opposite. Disease unknown to some parts were brought there from other parts and the Black Death also made its way up the Silk Road resulting in millions of deaths. The well managed and travelled Silk Road also aided many new forces to invade lands, such as the Mongols who established their bases all along the major cities on the road. Yet no matter who the rulers are, the traders kept trading and just adjusted their lives accordingly, after all it didn’t really matter who you had to pay tributes to as long as you get to sell and buy what you need and want.

At some point the Silk Road became more dangerous and treacherous, with bandits robbing traders and travellers and selling them into slavery, and the different empires chose trade at sea for a while resulting in a quieter time along the Silk Road, until the losses at sea became more expensive due to storms and pirating of ships and cargo. Believe it or not it was the camel that saved the Silk Road. Here amongst us is this beast that can walk for days and survive in severe conditions and carry huge amounts of weight. It was the solution to many problems on land and the camel became one of the most important commodities on the Silk Road and its unlikely savior. From the time of using camels until the production of motor cars, the camel remained the preferred mode of transport for merchants in the Middle East along the Silk Road.

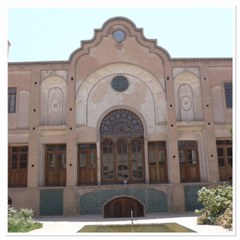

When the Ottomans took control of the area the Grand Bazaar in Turkey became the hot spot for Silk Road trade, because here East and West met and wealthy customers and merchants came from all over to meet in this most interesting melting pot of cultures.

“One vivid account comes from a French traveler in 1877, during the last years that the Grand Bazaar could still be seen in its original form. The writer, M. de Gasparin, is an incurable romantic. But there is clearly enough color in the bazaar to spark any imagination:

“An Arab, with his spear in hand, sitting surrounded by the Persian shawls which he brought by his caravans, used to walk after a long row of camels in the desert. Another merchant is from the depths of Central Asia. Another one, with a thin face and pale complexion, has passed the sand and the seaside beaches of Syria on horseback and brought golden colored silk from Lebanon and soft clothes and pleasant scarves from Tyre and Sidon ... Egypt has sent that nearly black-skinned merchant who has brought the heavy cloth of that country, a mixture of silk and wool. This thin-faced bronze, tanned man comes from Morocco, leaning against milk-white threads and lapis blue dresses. Wherever these men may have been, whatever adventures they may have lived and whichever foreign country has injected the traces of other skies into their faces, their brows have lost nothing of their majestic nobility and their meaningful eyes have lost nothing of the depth that comes from authority, self-respect, and self-assurance. These merchants do not call the passers-by to their shops. They do not even have an inviting attitude; one could sense no greed in them, nor any worry in their posture … If a buyer came, ‘Masallah,’ if no one entered their shops, ‘So what?’”

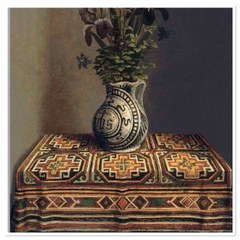

There were rugs from Central Asia, from the Caucasus, from Anatolia. There were rugs smuggled by the tons across the border from Persia, the Ottoman Empire’s great eastern rival. The border was often officially closed but the carpet trade was so lucrative that both sides turned to a third party – their Armenian populations – to act as the go-between for the business and let them freely cross the frontier."

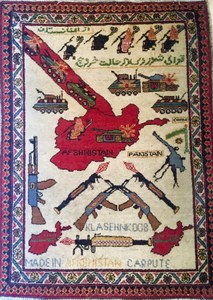

From here goods also flowed to Venice from where it would enter the insatiable European market. It is after all the constant demand for exotic Eastern items that kept the Silk Road and all its merchants, craftsmen, artists and partners going until the Europeans, tired of having to pay constant taxes, found their own way to the East. Then a new way and wave of doing business commenced that completely side-lined the Silk Road and all her partners. It tipped the scales of power into the hands of the West and one can argue that that is still the case. Yet the romantic, the mystical, the magical, the exotic Silk Road culture lives on in the many cultures that still live on it uninfluenced by modern life. We see it in their carpet designs, in their clothing and their art, and it takes us back to that time of wonder.

Sources: