Hamlet’s Mill, the epic work by Hertha von Dechend, professor of the history of science at the University of Frankfurt, and Giorgio de Santillana, professor of the history and philosophy of science at M.I.T., shows the link between myth and astronomy. They describe myth and folklore as the scientific language of yore, and point out that precession was the number one topic of discussion in ancient science and was known to ancient cultures around the world. Who knows exactly how or when ancient civilizations started using the stars for guidance on earth, but it is clear that they definitely understood the science of nature affecting us just as we affect nature around us (as above so below). Looking to the stars and ruling stars systems at particular times helped the humans to make sense of their daily lives and the presiding energies on earth. They paid homage to the ruling zodiac ages by building and making representations of it on earth, perhaps not so much as worshipping it as to acknowledge it and to pay respect to its influences on them. For the ancients the processions of zodiacal signs marked important changes and signs, and many of their empires and religions were shaped according the ruling energies of the time. We all know the story of the Three Wise Men who followed the star of Bethlehem to find the baby Jesus. This was an important star to the three magi (who were among a group of top Persian scientists, mathematicians, alchemists and astrologists of their time) because it signalled the movement into a new era. As the Age of Aries changed into the Age of Pisces, this star brought with it the start of a religion that would completely change life on earth and would become the largest in the modern world. This bright star appeared at the start of the Age of Pisces and Christianity has always used the fish as its symbol.

Another zodiacal sign that have lasted for millennia and is still very popular is that of the Lion and Sun. In astrology the Sun is the ruling planet of the zodiac sign, Leo, therefore combining both in a symbol is a clear indication that the particular art was made under the influence of this star sign, possibly when it was the ruling age or when it was a Leo ruling era. Whereas Scorpio, (previously discussed) is a feminine, mysterious, seductive and deadly sign, Leo is overpoweringly masculine, powerful and regal. All empires and religions linked to this sign generally attempted to outwardly reflect these qualities. Let’s have a look at some examples of where the sign of Leo have influenced past civilizations:

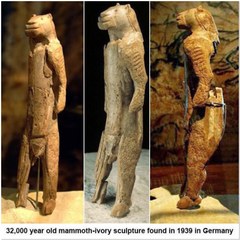

The oldest anthropomorphic idol found so far is the lion headed man called the "lion man" (German: Löwenmensch, literally "lion human"). This is an ivory sculpture that is both the oldest known zoomorphic (animal-shaped) sculpture in the world, and the oldest known uncontested example of figurative art yet discovered. Archaeologists have also interpreted the sculpture as anthropomorphic, giving human characteristics to an animal, and proposing that this could have been a representation of a lion headed deity. The figurine was determined to be about 40,000 years old by carbon dating. It was carved out of mammoth ivory using a flint stone knife. There are seven parallel, transverse, carved gouges on the left arm. It is now in the museum in Ulm, Germany. This sculpture was made around the time of the age of Leo 36720 – 34560BC.

Another giant leonine statue of which the exact age has not yet been determined is the Sphinx in Egypt. The riddle of the Sphinx of Gizeh, resting by the pyramids like a watchdog, has remained unsolved since the times of the pharaohs. The important point about this story is that the Sphinx was buried to its neck in sand thirty-seven centuries ago. This speaks for the very ancient origin of the Lion-Man even in that distant epoch. The ancient Egyptians called the monument 'Hu' or protector. Modern geologists project that the Sphinx is probably 9,000 years old (placing it close to the last age of Leo) but there are other Egyptologists that believe that the Sphinx was built in the preceding age of Leo making it around 40,000 years old. Until such time as the actual age is determined the first mentioned age calculation must suffice. Both of the ages refer to an age of Leo where the art of the civilizations reflected its influence. The body of the remote Ancient Egyptian God of Creation, Hu, was deliberately leonine as the superbly crafted lion was a symbol of Power and Strength. The lion was omnipotent. Even today the lion is referred to as "King of the Beasts". The face of the Creator with the distinctive Osiris Beard, and the Red Crown of the Creator, are the hallmarks of the remote Ancient Egyptians.

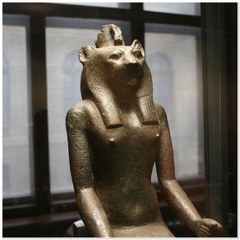

Ra is the ancient Egyptian sun god. By the Fifth Dynasty in the 25th and 24th centuries BC, he had become a major god in ancient Egyptian religion, identified primarily with the noon sun. In a myth about the end of Ra's rule on the earth, Ra sends Hathor as Sekhmet (a leonine goddess) to destroy mortals who conspired against him. Sekhmet later was considered to be the mother of Maahes, a deity who appeared during the New Kingdom period. He was seen as a lion prince, the son of the goddess.

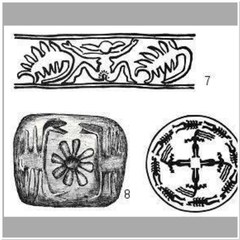

Inanna was the ancient Sumerian goddess of love, beauty, sex, desire, fertility, war, combat, justice, and political power. She was later worshipped by the Akkadians, Babylonians, and Assyrians under the name Ishtar. She was known as the "Queen of Heaven" and was the patron goddess of the Eanna temple at the city of Uruk, which was her main cult centre. She was associated with the planet Venus and her most prominent symbols included the lion and the eight-pointed star. The rosette was another important symbol of Inanna, which continued to be used as a symbol of Ishtar. (The eight point star and eight petal rosette is a very common design in Persian carpets and art and we will discuss this in more detail in a future article). As menionted, Inanna-Ishtar was associated with lions, which the ancient Mesopotamians regarded as a symbol of power. Her associations with lions began during Sumerian times. During the Akkadian Period, Ishtar was frequently depicted as a heavily armed warrior goddess with a lion as one of her attributes.

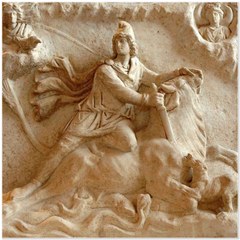

In Hellenistic times, Aion Chronos was identified with the Old Persian time-god, Zurvan, a god that predated Mithra. The ancient Persians discerned two aspects of this supreme deity: Zurvan akarana, Infinite Time, and Zurvan daregho-chvadhata, Time of a Long Dominion. The latter was the cause of decay and death, and was sometimes even identified with Ahriman, the principle of evil in the later Persian religion, Zoroastriasm. Zurvan is depicted with a Lion head and human body holding a staff, with a snake encircling his body.

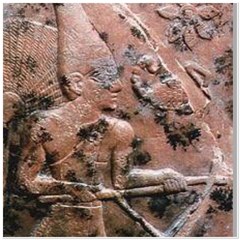

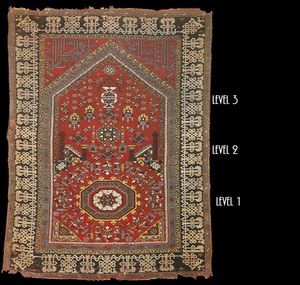

In Iran the simultaneous representation of the lion (Shir e Iran) and the Sun has often been attributed to the post-islamic era, especially from the 13th century AD. In reality, the Lion-Sun motif already appeared together during the Achaemenid era. The oldest evidence for the simultaneous representation of the Lion and the Sun in Iran date to a cylinder of King Sausetar in 1450BC. The image is that of a sun-disc resting on a base flanked by two wings, with two lions guarding at the base. The Lion was an Iranic mythological symbol of strength and virility. The same type of Lion hunter theme that is found at Persepolis is also in the arts of North Iranic peoples such as the Scythians of ancient Ukraine and south Russia. The sun is a manifestation of the ancient Iranic god Mithras, whose cult predates the Achaemenid dynasty. In a sense the manifestation of Mithras and Anahita (often depicted with a lion) go beyond mere tribal symbols – they are an expression of ancient Iranian mysticism and theology. Mithra is perhaps one of the best known Iranic gods and was later widely worshipped in the Roman Empire. He was regarded as the god who controls the order of the cosmos. In Mithraic rituals there are seven levels of initiation for initiates. The fourth level is called the Lion. The Lion wore a long scarlet cloak and was always 'of an arid and fiery nature'. His symbol was a fire-shovel. Porphyry, records: “When those who are being initiated as Lions have honey instead of water poured over their hands to cleanse them, then are the hands kept pure of all evil, all crime and contamination, as becomes an initiate. Since fire is purifying, the fitting ablution is administered to them, rejecting water as being hostile to fire. And they also cleanse his tongue of sin with honey.” The story of Samson from Judah (the lion) seems to fit the symbolism of the Mithraic level of the Lion. Firstly he battles with and kills a lion and on passing the lion’s carcass later he finds a beehive inside it. Any beekeeper will confirm that bees will never nest in a rotting carcass so the story of Samson could be symbolic. Even more interesting is the riddle Samson makes for the Philistines using his encounter with the lion, in the Old Testament:

(Book of Judges 14:14): The Riddle

And he said unto them,

Out of the eater came something to eat,

and out of the strong came something sweet.

And the answer was:

What is sweeter than honey?

What is stronger than a lion?"

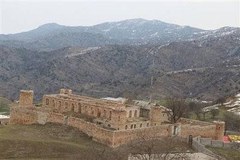

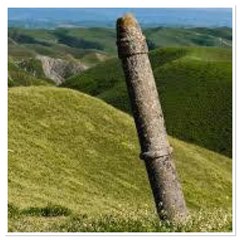

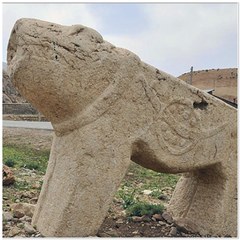

Using lion statues as guardians is also a popular theme throughout antiquity, from guarding doors to gates to graveyards. There is a stone lion - one part of the 'Lions Gate'- sitting on a hill where a Parthian era cemetery (247C – 224AD) is said to have been located in Hamadan. When first built, this statue had a twin counterpart for which they both constituted the old gate of the city. The gates were demolished in 931CE as the Deylamids took over the city. Mardāvij unsuccessfully tried transporting one of the lions to Ray. Angered by the failure to move them, he ordered them to be demolished. One lion was completely destroyed, while the other had its arm broken and pulled to the ground. The half demolished lion lay on its side on the ground until 1949, when it was raised again, using a supplemental arm that was built into it

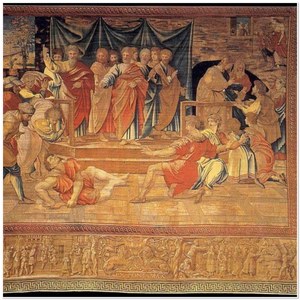

Located in the Eastern Wall in Jerusalem, near the gate’s crest are four figures of (some say) leopards who are mistaken for lions, two on the left and two on the right. They were placed there by Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent to celebrate the Ottoman defeat of the Mamluks in 1517. Legend has it that Suleiman's predecessor Selim I dreamed of lions that were going to eat him because of his plans to level the city. He was spared only after promising to protect the city by building a wall around it. This led to the lion becoming the heraldic symbol of Jerusalem. However, Jerusalem already had been, from Biblical times, the capital of the Kingdom of Judah, whose emblem was a lion (Genesis 49:9). According to the Hebrew Bible, the throne of King Solomon was covered with ivory, overlaid with gold and featured lions on each side of the armrests. Six steps led up to it and twelve lions stood on them, one at either end of each step. (I Kings 10:18-20.) The biblical passage claims nothing like it had ever been seen before.

The Persian lion (now known as the Asiatic lion) was once quite common throughout their historic range in Southwest, South and Central Asia and are believed to be the ones depicted by the guardian lions in Chinese culture. These incredible creatures were introduced to the Han Dynasty by envoys from Parthia and were given the name “Shi” which derives from the Persian word for lion, “Shier”. The Buddhist version of the Lion was originally introduced to Han China as the protector of dharma and these lions have been found in religious art as early as 208 BC. Gradually they were incorporated as guardians of the Chinese Imperial dharma. Lions seemed appropriately regal beasts to guard the emperor's gates and have been used as such since. There are various styles of guardian lions reflecting influences from different time periods, imperial dynasties, and regions of China. These styles vary in their artistic detail and adornment as well as in the depiction of the lions from fierce to serene. The guardian lions have incorrectly become known over time as Foo Dogs.

Lion tombstones (šir-e sangi; or bardšir, “stone lion” in Lori) are tombstone found mostly on the graves of Lor and Qašqāʾi nomads in the west, southwest, and parts of southern Persia. It is difficult to account for the history of the use of stone lions by the Baḵtiāris to mark their tombstones. They were made mostly by professional, non-Baḵtiāri stonemasons who travelled seasonally between Baḵtiāri territories. Their use had stopped by the mid-20th century, but they began to appear again in recent years. These stone lions continue to have an enduring significance today. In the absence of a written history, they represent one way in which the Baḵtiāris are able to celebrate their past. Songs and ceremonies associated with funereal traditions, such as traditional lamentations (gāgeriva), are extremely important in recording the events of the Baḵtiāri’s past that are related to these lions. Thus the stone lions evoke for the Baḵtiāris the memory of an idealized past wrought with heroics and wars, a stark contrast to their contemporary situation.

Historically and culturally speaking, the Lion and the Sun have existed as potent mythological symbols of Iran for thousands of years. While true that the background colors of Iranian flags have varied across the centuries, the Lion and Sun motifs have endured the test of time. The lion and sun motif is based largely on astronomical and astrological configurations, and the ancient zodiacal sign of the sun in the house of Leo. This symbol, which combines "ancient Iranian, Arab, Turkic and Mongol traditions", again became a popular symbol in the 12th century. According to Afsaneh Najmabadi, the lion and sun motif has had "a unique success" among icons for signifying the modern Iranian identity, in that the symbol is influenced by all significant historical cultures of Iran and brings together Zoroastrian, Shia, Jewish, Turkic and Iranian symbolism.

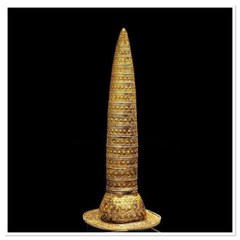

The male sun had always been associated with Iranian royalty: Iranian tradition recalls that Kayanids had a golden sun as their emblem. From the Greek historians of classical antiquity it is known that a crystal image of the sun adorned the royal tent of Darius III, that the Arsacid banner was adorned with the sun, and that the Sassanid standards had a red ball symbolizing the sun. The Byzantine chronicler Malalas records that the salutation of a letter from the "Persian king, the Sun of the East," was addressed to the "Roman Caesar, the Moon of the West". The Turanian king Afrasiab is recalled as saying: "I have heard from wise men that when the Moon of the Turan rises up it will be harmed by the Sun of the Iranians." The sun was always imagined as male, and in some banners a figure of a male replaces the symbol of the sun. In others, a male figure accompanies the sun. Similarly, the lion too has always had a close association with Iranian kingship. The garments and throne decorations of the Achaemenid kings were embroidered with lion motifs. The crown of the half-Persian Seleucid king Antiochus I was adorned with a lion. In the investiture inscription of Ardashir I at Naqsh-e Rustam, the breast armour of the king is decorated with lions. Further, in some Iranian dialects the word for king (shah) is pronounced as sher, homonymous with the word for lion. Islamic, Turkish, and Mongol influences also stressed the symbolic association of the lion and royalty.

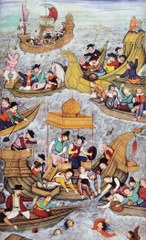

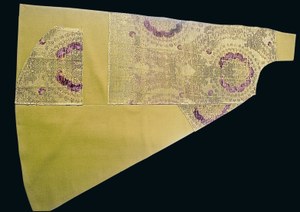

In between the Sasanid dynasty and China lived an Iranian tribe called the Sogdians who became very experienced merchants because they were based on the Silk Road and many goods passed through. They were also expert craftsman and weavers and realizing the popularity of the Sasanid pearl roundel textiles, they too started producing it. Due to their relations with Europeans, they realized that the pearl roundel appeals to all religious denominations, not for religious values but for secular class values. So, they adjusted the design a little to make it more secular and commercial assuring a wider customer base. The lion (without wings) was introduced in the medallion because a lion, the king of beasts, is often used both in the East, and in the West, personifying power and prosperity. It is one of the most used symbols of force throughout thousands years. Wearing clothes with the figure of a lion was understood everywhere as a personification of supreme power and glory. We can assume that the popularity of the lion in European flags and coats of arms, came from this initiative of the Sogdians.

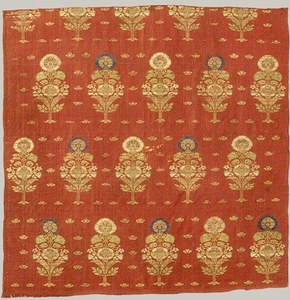

The lion and sun symbol appears in the 12th century, most notably on the coinage of Kaykhusraw II, who was Sultan of the Seljuk Sultanate of Rûm from 1237 to 1246. These were "probably to exemplify the ruler's power." In Safavid times, the lion and sun stood for two pillars of the society, state and religion. It is clear that, although various alams and banners were employed by the Safavids during their rule, especially the earlier Safavid kings. By the time of Shah Abbas, the lion and sun symbol had become one of the most popular emblems of Persia. For the Safavids, the Shah had two roles: king and holy man. This double meaning was associated with the genealogy of Iranian kings. Two males were key people in this paternity: Jamshid (mythical founder of an ancient Persian kingdom), and Ali (Shi'te first Imam). Jamshid was affiliated with the sun and Ali was affiliated with the lion (Zul-faqar). Since Ottoman sultans, the new sovereigns of 'Rûm', had adopted the moon crescent as their dynastic and ultimately national emblem, the Safavids of Persia, needed to have their own dynastic and national emblem. Therefore, Safavids chose the lion and sun motif. Besides, the Jamshid, the sun had two other important meanings for the Safavids. The sense of time was organized around the solar system which was distinct from the Arab-Islamic lunar system, as it still is today. Astrological meaning and the sense of cosmos was mediated through that. Through the zodiac the sun was linked to Leo which was the most auspicious house of the sun. Therefore, for the Safavids, the sign of lion and sun condensed the double meaning of the Shah—king and holy man (Jamshid and Ali)—through the auspicious zodiac sign of the sun in the house of Leo and brought the cosmic-earthy pair (king and Imam) together.

The royal seal of Nadir Shah in 1746 was the lion and sun motif. In this seal, the sun bears the word Al-Molkollah (Arabic: The earth of God). Two swords of Karim Khan Zand have gold-inlaid inscriptions which refer to the: "... celestial lion ... pointing to the astrological relationship to the Zodiac sign of Leo ..." Another record of this motif is the Lion and Sun symbol on a tombstone of a Zand soldier.

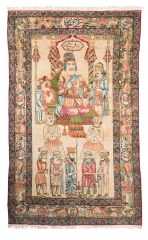

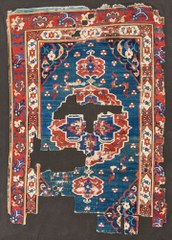

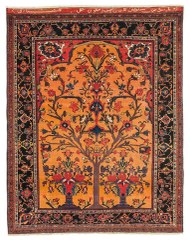

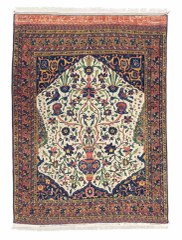

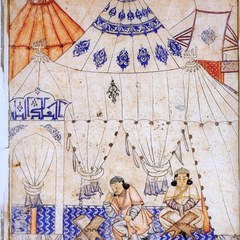

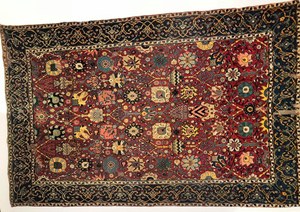

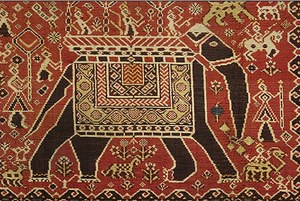

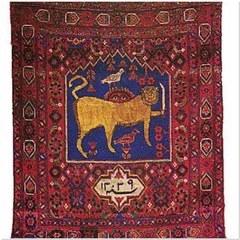

Lion rugs (gabba-ye širi), is a group of Persian rugs with the image of the lion as the main motif. Although in the past lion rugs were made in most parts of Iran, the majority of the existing lion rugs are the work of Baḵtiāri and Qashqāʾi tribes in southwest Iran and were woven during the 19th and 20th centuries. According to the pertinent literature, however, lion rugs have been known to Iranians since at least the 12th century. Anwari (ca. 1126-ca. 1189) in a poem compares the lion rug of a palace with the constellation Leo in honor and in glory, and in another poem he emphasizes that the lion of the celestial palace cannot compete with the lion of a (royal) carpet. The oldest dated lion rug, however, goes back to 1796. This rug was made for a khan (tribal chieftain). It is possible that many of the existing lion rugs were made for khans, as there is an old tradition of spreading lion rugs in royal courts. The khans followed that tradition and spread lion rugs in their tents as a sign of power.

Sources