The legend of the discovery of silk in China goes back to 4000 BC: Lei Zu, the wife of Emperor Huang Di, the Yellow Emperor, was sipping her midday tea under a mulberry tree when something unexpectedly fell into her cup. She looked to see what it was she saw a cocoon starting to unravel slowly. After the silk cocoon completely unravelled it stretched the entire garden long and Lei Zu saw the silkworm that was the creator of this magnificent silky thread. She imagined that this fine thread could be used to make fine gowns and from that day on she became the inventor of sericulture, the cultivation of silkworms. The Chinese for centuries enjoyed and refined all the different types of weaving that could be done with this extraordinary material and they experimented with all the different types of objects that could be made from it too, from clothing to paper, etc.

Silk has bedazzled the world for millennia and we still cannot get enough of its look and feel, be it clothing, bedding, décor and of course, carpets. Evidence that this phenomenon has existed from at least 3,000 to 4,000 years was found in the form of a silk cocoon cut in half at the Yangshao cultural site in Xia County, Shanxi, China. The species was confirmed as Bonbyx mori, the humble domesticated silkworm that produces this thin strain of beauty. The Shang and Zhou Dynasties of China produced silk items on a large scale and the weaving techniques became more sophisticated too. Just how important and precious this medium was for China and it’s trading, is evident in the find of Shang Dynasty silk (c. 1600 to 1046 BCE) in an Egyptian tomb.

It would be the Han Dynasty (206 BC–220 AD) that really made silk an International commodity when they started the Silk Road on land but also improved their sea trading that would later be called the Maritime Silk Road. “Evidence found in Chinese literature, and archaeological evidence, show that cartography existed in China before the Han. Some of the earliest Han maps discovered were ink-penned silk maps found amongst the Mawangdui Silk Texts in a 2nd-century-BC tomb”. Just how far this Maritime Silk Road progressed before the expansive land Silk Road, is evident in the Roman glassware that has been found at Han-era tombs. “The weave of some Han period pieces, with 220 warp threads per centimetre, is extremely fine. The cultivation of the silk worms themselves also became more sophisticated from the 1st century CE with techniques used to speed up or slow their growth by adjusting the temperature of their environment. Different breeds were used, and these were crossed to create silk worms capable of producing threads with different qualities useful to the weavers”. The Han Dynasty ensured that China held the global monopoly on silk production and promptly executed anyone who tried to smuggle the silkworms or their secret out of the country.

After the Han Dynasty’s collapse various periods of war reigned in China until the Tang Dynasty came to power (AD 618–907). The Tang s did much for Chinese trade and trading partners and through their efforts the Silk Road was reopened and expanded to reach their neighbour, Persia, and from Persia it reached the West. The Silk Road thereafter became the legend it is today and through this route China gained many new technologies, cultural practices, rare luxury items as well as contemporary items. “From the Middle East, India, Persia, and Central Asia the Tang were able to acquire new ideas in fashion, new types of ceramics, and improved silver-smithing. The Chinese also gradually adopted the foreign concept of stools and chairs as seating, whereas the Chinese beforehand always sat on mats placed on the floor. To the Middle East, the Islamic world coveted and purchased in bulk Chinese goods such as silks, lacquerwares, and porcelain wares. Songs, dances, and musical instruments from foreign regions became popular in China during the Tang dynasty. These musical instruments included oboes, flutes, and small lacquered drums from Kucha in the Tarim Basin, and percussion instruments from India such as cymbals.” Via the Silk Road Buddhist knowledge was imported to China, as well as many other influences. There was even a Turkic-Chinese dictionary available for serious scholars and students and Turkic folksongs became a great source of inspiration for Chinese poetry. Thousands of foreigners immigrated to Chinese cities during the Tandy Dynasty, including Persians, Arabs, Hindu Indians, Balys, Chams, Jews, etc.

The Tang Dynasty also strengthened and expanded the Maritime Silk Road. “Although Chinese envoys had been sailing through the Indian Ocean to India since perhaps the 2nd century BC, it was during the Tang dynasty that a strong Chinese maritime presence could be found in the Persian Gulf and Red Sea, into Persia, Mesopotamia (sailing up the Euphrates River in modern-day Iraq), Arabia, Egypt, Aksum (Ethiopia), and Somalia in the Horn of Africa.”

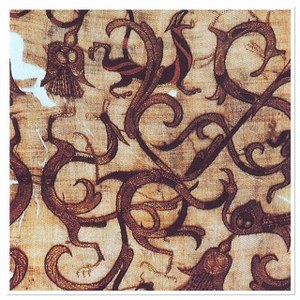

With China still holding the monopoly on the silk trade as well as the secret of how to cultivate the silkworm, the Western Empires saw their much needed funds flow East in mountains, so the Byzantine Empire sent two monks to China to learn what the secret of silk is. These two monks managed to smuggle some silkworms west and so began the silk production there, however, they did not know China’s secret of unravelling the cocoons in such a way that only a single strand of silk remained and although the Byzantines used Sasanian techniques to produce fantastic textiles, it was still inferior to Chinese silk.

Silk inspired many arts and its praise is sung in this poem by Master Xun of the Warring states Period (476 – 221 BC):

How naked its external form,

Yet it continually transforms like a spirit.

Its achievement covers the world,

For it has created ornament for a myriad generations.

Ritual ceremonies and musical performances are completed through it;

Noble and humble are distinguished with it;

Young and old rely on it;

For with it alone can one survive.

Sources and extracts:

- http://www.visiontimes.com/2017/05/20/silk-weaving-one-of-ancient-chinas-greatest-inventions.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Han_dynasty

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Silk_Road

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tang_dynasty

- http://www.ancient.eu/Silk/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_China

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_silk