Now, you know, once a fellow gets it into his head that he wants something, he can’t get it out again. And when he’s a collector, he won’t even stop short of murder if necessary. That’s what makes collecting a truly epic pursuit.

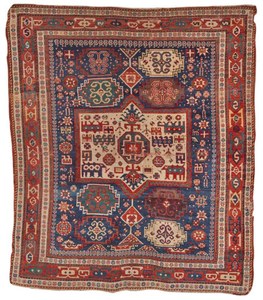

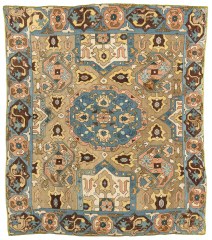

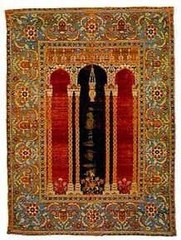

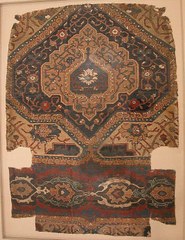

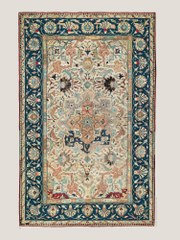

Ehem, said Doctor Vitasek. I know a thing or two about Persian carpets, Mrs. Taussig, and I can tell you, they’re not what they used to be. Today those idlers in the orient aren’t going to put themselves to the trouble of dying wool with insect reds, with blues from indigo plants, or with extracting yellow from saffron, much less to working with camel urine and wood extracts to get any of the other noble organic colors. Not even the wool is what it used to be. And, if I start talking about patterns and motifs, well, that’s enough to make anyone weep. It’s all lost, all that art of the Persian carpet. It is only the old pieces, the ones made before the 1870s, that have any value now, and you can only manage to buy one of them when some old family which has been passing one down, generation by generation, lets it go for what they call “family reasons,” as they like to term their debts. Listen, once I was visiting Rozemberg castle and there I saw a genuine Transylvanian – one of those little prayer carpets the Turks were weaving in the 17th century when they were conquering everything. All over the castle there were tourists stamping around in hobnail boots -- all around that carpet! – and not one of them had the slightest idea of how valuable it was – now, isn’t that enough to make you cry? But do you know the strangest thing of all? One of the world’s most priceless rugs happens to be right here in Prague, and nobody even knows it exists!

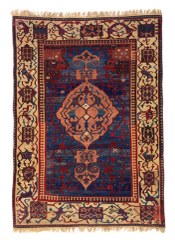

It’s true. I know all the carpet merchants in our country, and sometimes I go around to see what they have in stock. You know, sometimes the agents in Anatolia and Persia get hold of an antique piece that’s been stolen from a mosque or somewhere, and they wrap it up inside some cheap material priced by the meter and then they sell the whole bundle, no matter what’s inside, by weight alone to slip it past customs. And I start thinking to myself, what if they’ve wrapped up a Bergama! That’s why, sometimes, I just drop in on carpet seller here or there, sit down on a mountain of carpets, have a smoke, and just watch how he sells his rugs – just like he's selling sacks of coffee – all the Bucharas, Sarouks, Tabrizes. And now and then I’ll just look down and say, so what have you got down here, this gold one? And, what do you know, it’s a Hamadan! And that was how I once dropped in on a certain Madame Severynova, who keeps a little courtyard shop in Old Town and who sometimes has some fine Karamans and kilims. She’s a round, jolly lady, very talkative, and she has a poodle so fat it makes you ill. You know, one of those pudgy mutts which are so testy and asthmatic and bark so crossly – I can’t say I like them much. Listen, have you ever in your life seen a young poodle? I haven’t and I’d even argue that every poodle, like every police inspector, accountant, and tax collector, is born old, it’s like they don’t even belong to the dog species! Still, I wanted to keep good relations with Mrs. Severynova, so I always sat in the same corner where Amina the fat poodle was wheezing and snoring on a big, folded-up carpet and I would scratch her back – that, at least, was something Amina liked. And one time I said, Mrs. Severynova, these must be bad goods that I’m sitting on, they haven’t sold for three years. And she said, that’s nothing. That carpet over there has been lying in the corner a good ten years, and it’s not even my carpet. Oh, I said, you mean it’s Amina’s now? And she smiled and said, not at all, it belongs to a certain lady who has no room for it in her home and so she keeps it here. It’s in my way but at least it’s something Amina can sleep on. Isn’t that right Amina, dear?

It was at that moment that I reached out my hand and lifted up the edge of what Amina was lying on, even though she immediately started snarling. So what kind of old carpet is it, I asked, can’t I have a look? Why not, Madame Severynova said, and she grabbed up Amina in her arms. Come on, Amina, sweetie, he’s only looking. But Amina growled again. Stop it Amina, she ordered. Quiet down, you silly thing.

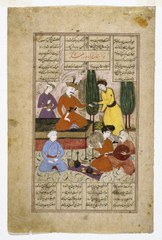

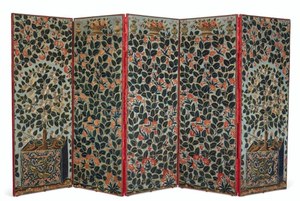

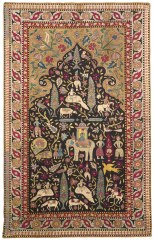

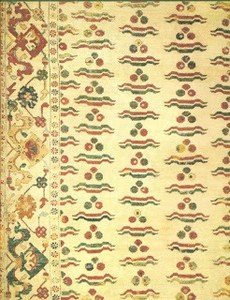

All that time, I was staring at the carpet and my heart almost stopped beating. It was a white Anatolian, from around the 17th century, and worn through in places. But it was one of those antique bird carpets, one of those white Anatolians that are decorated either with a field of birds or with a field of Qintamani , but never both together. That's the rule, to keep separate the sacred from the profane -- because they say the Qintamani, that triangle of three dots floating on two wavy lines, is a religious symbol that goes right back to the Buddhist times of Central Asia. But on this carpet, I know it sounds impossible, there were BOTH birds and Qintamani at the same time! The whole thing gave off a feeling of something powerful, of a miracle or, at the very least, of something utterly forbidden ... whatever it was, I can tell you, this piece was an extraordinary rarity! And it was at least five by six meters in size, a beautiful white shade, with turquoise blue, cherry red ... I went to stand by the window so Madame Severynova would not see the expression on my face. And then I said, as casually as I could: what an old rag, Madame Severynova, it must really be in your way. You know, I could take it off your hands, since you don’t really have space for it here.

That’s going to be difficult, Madame Severynova replied. This carpet is not for sale, and the lady who owns it is always traveling, she’s in Meran or Nice, and I don’t even know when she is home. But I'll try to ask her. Oh, would you be so kind, I said as disinterestedly as I could, and I went home. Just so you know, it’s a point of honor for a collector to get something rare and valuable for just a song. I know one very esteemed and wealthy man who collects books, for example. He can pay several thousand dollars for a collectible without the slightest show of emotion. But whenever he is able to wrangle a first edition copy of the works of the poet Joseph Krasoslav Chmelensky from some rag picker for a just a few cents, he jumps for joy. That’s the kind of sport it is -- like hunting that most elusive of deer, the alpine chamois. And all that is how I got it into my head that I had to have that carpet very cheaply and that afterward I would bequeath it to a museum, because something so rare really doesn’t belong to anyone. Only I did want one thing out of it: a little memorial plaque with the inscription ‘the gift of Doctor Vitasek.' After all, doesn’t everyone have some ambition?

But I’ll admit, my head was spinning. It took all my efforts to keep myself in check and not run back to that shop the very next day to ask again about the Qintamani with birds. I couldn’t think of anything else. But every day I told myself, just hang on for one more day. I was putting myself through hell, but sometimes people love to torture themselves. And then suddenly – even worse – after about two weeks a horrible thought hit me, what if someone else discovered that bird carpet? And then I flew over to Madame Severynova. I literally burst through her door.

What on earth’s going on? the surprised lady asked me. But I replied, as casually as I could, that I just happened to be in the area and remembered about that old white carpet. Would the owner sell it? Madame Severynova shook her head. What do I know, she said, she’s is in Biarritz now and no-one knows when she will return. Meanwhile, I was trying to steal a look, is the carpet still there, and sure enough it was, with Amina lying on it, fatter and more scabious than ever, waiting for me to come scratch her back.

Sometime later, I had to make a trip to London, and as soon as I arrived I dropped in on Mr. Keith, you know, the Sir Douglas Keith who is today one of the greatest experts on oriental carpets. My good sir, I said to him, what value would you assign a white Anatolian with a Qintamani and bird design, with a size that exceeds a full five by six meters square? And Sir Douglas just stared at me though his thick glasses and then, almost in a fit of anger, blurted out, "Why nothing, my man!" "What do you mean? I asked dumbfounded. Why on earth would it be worth nothing?" And Sir Douglas was almost shrieking now: "Because the carpet you describe cannot possibly exist in that size! Dear fellow, you must know that the largest Qintamani and bird carpet that I have ever seen barely measures three by five meters!" I admit, I had to blush with joy. And now it was my turn: My dear man," I said, "let’s just imagine such a piece of that size did exist, what would be its price?" "But, I’ve already told you, nothing," Mr. Keith cried out again, "because that piece you describe would be absolutely unique and how can you put a value on something that’s unique? It could as well be worth 1,000 pounds as 10,000, how would one know? In any case, such a carpet does not exist, Good day, Sir!"

You can imagine in what a mood I returned home. Good God, I had to have this rug with the Qintamani now! What a catch it would be for any museum! And now, just imagine my situation. I couldn’t just go and beg for it, because that would not be sporting for a collector. And Madame Severynova had no particular interest in selling this old rag when it was so dear to her Amina. And that cursed woman who owned the carpet was always in motion, from one health spa to another, from Meran to Ostend, from Baden to Vichy – that woman must have had a whole medical catalogue of symptoms at home to inspire her and keep her in perpetual movement.

By this time, I was going about once every fortnight to Madame Severynova’s shop just to peek in and make sure that carpet with all its birds was still in its corner, as well as to rub down that odious Amina until she whimpered with joy. And just so that all this didn’t become too noticeable, each time I went I also purchased a little carpet. Certainly, I already had at home more than enough Shirazes, Shirvans, Mosuls, Kabristans, and all kinds of other by-the-meter stuff – and I even had a classic Derbent that you wouldn’t exactly find every day plus one beautiful antique blue Khorosan. But what I experienced for two years trying to get this Qintamani, well only a collector would understand. You know, the agony of love is nothing compared to the agony of collecting, and the only thing that is really strange is that, as far as I know, no collector yet has taken his own life. Instead, most live to ripe old ages. So, at least it must be a healthy passion.

One day Madame Severynova suddenly said to me: you know, Mrs. Zanelli, who owns that carpet, she was here. And I told her I might have a buyer for her white elephant that’s been cluttering things up so long. And she said, she wouldn’t think of it, it’s a family heirloom, and I should just leave it right where it is.

That is when I decided to run over to see that Mrs. Zanelli myself. But if I thought she was going to be a lady of the haut monde, well, in fact she was one of those nasty grannies with a purple nose, a wig, and some kind of strange tick, so that her mouth was constantly twitching up her left cheek all the way up to her ear. Your Grace, I said -- and all the time I couldn’t stop looking at how her mouth was dancing up her cheek -- I would be prepared to purchase that white carpet of yours; even though it is a poor specimen, it would go nicely in my ... my foyer, you know. And as I paused for her reply, I had the strange sensation that my own mouth was beginning to jerk and jump up on the left side. Whether her tick was infectious, or whether it was from excitement, I don’t know, but I couldn’t stop mine either.

How dare you! That dreadful woman squealed. Go! Go this instant! That carpet is a family heirloom ... from Grand Papa. If you don’t leave, I’ll call the police. I don’t sell carpets, here. I am a Zanelli! Hail Mary, let this man be gone! Listen, I ran down the stairwell from her apartment like a little boy, my eyes burning with sorrow and rage, what else could I do? For another whole year, I went by Madame Severynova’s and during that time Amina learned to grunt, she was already as fat as a sow and almost completely bald. Then, finally, after a year had passed, Mrs. Zanelli returned to town once more. This time I surrendered and did something of which, as a collector, I shall be ashamed of to the day I die. I sent my friend to see her, the lawyer Mr. Bimbal – he’s one of those kindly, whiskered fellows who inspires unbounded confidence among the ladies. My thought was that this sensitive soul could persuade Madame to part with her bird carpet for some reasonable amount of money. In the meantime, I waited downstairs, as excited as a fiancé waiting for an answer from his beloved. Three hours later, out came Bimbal, wiping the perspiration off his cheeks. You scoundrel, he hissed at me, I’ll throttle you! How did I ever agree to suffer three hours of listening to the entire family history of the Zanellis? And just so you know, he shouted, you’re never going to get that carpet! Seventeen Zanellis, all buried in Olsansky cemetery, would spin in their graves if their family relic went to a museum. Jesus and Mary, you owe me! And with that he left me.

Now you know once a fellow gets it into his head that he wants something, he can’t get it out again. And when he’s a collector, he won’t even stop short of murder if necessary. That’s what makes collecting a truly epic pursuit. And that is how I decided that I would simply have to steal that carpet with the Qintamani and birds. First, I staked out the surroundings, and I learned that the entranceway to the courtyard that housed Madame Severynova’s shop did not get locked up at until nine at night. And that was good, because I didn’t want to use a crowbar when I didn’t even know how to. From the entranceway, you could slip into a cellar where a fellow could hide until they closed up the whole place. Inside the courtyard, there was also a little overhang, and if you could get up onto the roof of that you could climb over to the neighboring courtyard, which belonged to a pub, and from there you could easily make your getaway to the street again unnoticed. It all looked quite easy, the only problem was how to actually break into the shop. For this, I bought a diamond, and at home I started practicing how to carve through glass windows.

Now please, don’t think that stealing is some simpleton’s business. I can tell you firsthand that it’s harder than operating on someone’s prostate or pulling out his kidney. The first thing is that nobody must see what you are doing. And the second thing, which is tied to that, is that there is plenty of waiting and other inconvenience. And the third thing is lots of uncertainty, you never know what might happen. I can tell you, this is a tough and underpaid profession. If I ever catch a burglar in my own apartment, I will take him by the hand and tell him gently, my man, why are you going to all this trouble? There are plenty of other, much easier ways to part people from their money.

I really don’t know how other people steal, but my own experiences aren’t very favorable. On the critical evening, as they say, I slipped into the courtyard in question and hid myself midway down the stairs leading to the cellar. At least that’s how you might describe it in a police report; in reality, it looked more like this: for a half-an-hour I loafed about in the rain near the entranceway, probably very conspicuously. Finally, I decided in desperation, a bit like someone decides to go and have a tooth pulled, to come out of my hiding place and then, straightaway, I nearly ran into a servant girl who was going out to the pub next door to fetch some beer. To calm her down, I muttered something endearing, like ‘you little rosebud,’ or ‘nice kitten,’ or something like that, and this had the unfortunate effect of startling her so badly that she took to her heels. I ran back down into the stairwell to hide, but those slovenly people in the building had put a trashcan full of ashes or some other rubbish where it was right in the way; so that the main event of my stakeout was the huge racket the trashcan made as it crashed over. At that moment, the servant girl returned with her order of beer and began shouting almost hysterically to the doorkeeper that some stranger had crept into the building. Fortunately, this stalwart fellow didn’t let himself be disturbed and announced loudly that it must be some drunk who had gotten lost going out of the pub. A quarter-of-an hour after that, spitting and yawning, the fellow locked up the courtyard door and all was quiet except for, somewhere up above, loud and lonely, the servant girl hiccupping. It’s strange how loudly some of these girls can hiccup; maybe it’s out of homesickness, who knows? I was starting to get cold and, besides that, the stairwell smelled sour and moldy; I groped around and found everything I touched was slimy. Then, oh my God!, I realized that our respected Dr. Vitasek, the specialist in diseases of the kidney and urinary tract, had just put his esteemed fingerprints all over the place. By the time I thought it must surely be midnight, it still was just barely 10 o’clock. I had firmly resolved that I wouldn’t begin my cat-burglary until midnight but by 11 o’clock I couldn’t hold out any longer and I set off to steal. You wouldn’t believe how much noise a man can make when he starts creeping around in the dark but, somehow, the whole house remained blessedly asleep. Finally, I got to the window I was aiming for and with a horribly loud scraping sound I began to cut the glass.

Suddenly, there was an explosion of barking. Jesus and Mary, Amina was in there!

Amina, I whispered, you monster, keep quiet, I’m only coming to scratch your back. But you can’t conceive how hard it is, in pitch blackness, to manipulate a tiny diamond so that it cuts twice in the same groove. Instead, mine was slipping all over the pane and it seemed to be making no progress until, all at once, I pressed a little harder and the whole glass shattered. Now everybody’s going to come running, I thought, and I looked around desperately for somewhere to hide. But, amazingly, nothing happened. Then I began to grow a lot calmer, to the point finally that I simply smashed in the next glass pane and opened the window. Inside, Amina was still letting out a half-hearted bark every now and then, but it was clear that she was only pretending to fulfill her duty. I crawled through the window and rushed over to that abominable creature. Amina, I half cooed, half hissed, where’s that damn back of yours? My love, it’s your dear friend! You monster, you like this, don’t you?

Amina squirmed with delight, that is if an overstuffed sack can be said to squirm. So, I whispered to her in a very friendly way, alright, you wretch give to me. And I tried to pull that priceless carpet out from under her. But now Amina must have suddenly understood I was talking about HER property. She started growling; it wasn’t barking it was really growling. Jesus and Mary, Amina, I said to her quickly, be quiet you beast. Just wait a second, I’ll make you a bed of something much better. And rip! I pulled down a dreadful, shiny Kirman which Madame Severynova kept hanging on the wall and which she considered the rarest piece in her shop. Look, Amina, I whispered, now here’s something to really sleep on. Amina looked at me with interest but just as soon as I stretched out my hand for her carpet there was another growl so loud it could be heard clear across town. There was nothing to do but start scratching that monster again, this time with a special, luxurious rubdown that put her into ecstasy. Then I grabbed her up in my arms. But as soon as I reached for that white, one-of-a-kind Qintamini and Birds, she gave off an asthmatic wheeze and then, I swear, began cursing me. By God, you monster, I said, almost beside myself, I’m going to have to murder you!

Now listen, I don’t understand this myself. I looked down at that vile, fat, repulsive thing with the wildest hatred I have ever felt, but I couldn’t bring myself to act. I had a good knife, I had a belt around my waist, I could have cut that monster’s throat or I could have strangled it, but ... instead I just sat down next to her on that divine carpet and scratched behind her ears. You coward, I muttered to myself, with just one motion, maybe two, she would be out of the way; you’ve operated on so many people and seen so many of them off, in agony and in pain, why can’t you dispatch a poor, simple dog? I gnashed my teeth, trying to work myself up to it but in the end I just broke down in tears, maybe out of shame. And Amina just whimpered happily and licked my face.

You miserable, swinish, good for nothing carcass! I patted her mangy back and then I crawled back out the window. You could call it a strategic retreat, or a complete rout. My escape plan had been to hop up on the roof of the shed and use that to get over to the adjoining yard and then out through the pub, but I didn’t have an ounce of strength left, or maybe the roof was just higher than I’d originally thought. So, I slipped back down that stairwell leading to the cellar and stayed there till dawn, half-dead with exhaustion. What I fool I am! I could have slept comfortably in the shop on top of all those carpets, but it didn’t occur to me. At daybreak I heard the portiere opening up the gate. I waited a moment and then I headed out. The doorkeeper was still there, lingering in the entryway, and when he saw a stranger slipping out past him he was so surprised he forgot even to make a fuss.

A couple of days later I visited Madame Severynova. Bars had been put on the windows of her shop but otherwise everything was as before. That dreadful toad of a dog was wallowing all over the holy Qintamini and when she spotted me she started wagging that fat sausage that is politely called her tail. My dear Sir, Madame Severynova beamed at me, just look at our priceless Amina, she’s worth every bit of her weight in gold. A treasure! Do you know that the other night some thief crept through the window and Amina chased him off? I wouldn’t give her up for anything in the world. But she likes you, doesn’t she, Sir? You know an honest gentleman when you see one, don’t you Amina?

And that is all there is to it. That one-of-a-kind carpet is still lying there today. It is, I’m certain, one of the rarest carpets in the world. And right to this day, that hideous, mangy, stinking Amina is on it, grunting with bliss. I’m sure one day she will finally suffocate under the weight of all her fat and then I'll try again. But first I’ll have to learn to file through iron bars.

Excerpt from Tea and Carpets blog

(Karel Capek, the well-known Czech journalist and novelist, published ‘Birds and Qintamani’ in his collection of short stories “Tales From Two Pockets” in 1929.)

![1. A Cassirer Reunion in Berlin - possibly for in celebration of an event (such as a wedding anniversary). [Source Peter Cassirer.] This has been dated as 1908. However, the presence of Lucie Oberwarth (26) suggests a date of no later than 1904 since she and Paul Cassirer were divorced on 21 May 1904.......Tentative identifications: 1. Bruno Cassirer, 2. Else Cassirer, 3. Agnes Cassirer, 4. Sophie Cassirer, 5.?, 6?, 8. Georg Eugen Cassirer?, 9. Anna Cassirer?, 11. Otto Bondi?, 12. Isidor Cassirer, 13. Lydia Cassirer, 14 Betty Cassirer?, 15 Toni Cassirer (nee Bondy,) 16 Richard Cassirer?, 17 Hedwig (Hede) Cassirer?, 23 Max Cassirer, 24. Walter Bondy, 25 Paul Cassirer, 26 Lucie Oberwarth, 27 Alfred Cassirer? 28 Ernst Cassirer, 29 Julie Bondi (nee Cassirer)?, 33 Lilly Diespecker?, 35 Kurt Goldstein or more probably Martin Cassirer?, 36 (left) Fritz Leopold Cassirer?, 36 (right) Julcher Cassirer? 1. A Cassirer Reunion in Berlin - possibly for in celebration of an event (such as a wedding anniversary). [Source Peter Cassirer.] This has been dated as 1908. However, the presence of Lucie Oberwarth (26) suggests a date of no later than 1904 since she and Paul Cassirer were divorced on 21 May 1904.......Tentative identifications: 1. Bruno Cassirer, 2. Else Cassirer, 3. Agnes Cassirer, 4. Sophie Cassirer, 5.?, 6?, 8. Georg Eugen Cassirer?, 9. Anna Cassirer?, 11. Otto Bondi?, 12. Isidor Cassirer, 13. Lydia Cassirer, 14 Betty Cassirer?, 15 Toni Cassirer (nee Bondy,) 16 Richard Cassirer?, 17 Hedwig (Hede) Cassirer?, 23 Max Cassirer, 24. Walter Bondy, 25 Paul Cassirer, 26 Lucie Oberwarth, 27 Alfred Cassirer? 28 Ernst Cassirer, 29 Julie Bondi (nee Cassirer)?, 33 Lilly Diespecker?, 35 Kurt Goldstein or more probably Martin Cassirer?, 36 (left) Fritz Leopold Cassirer?, 36 (right) Julcher Cassirer?](https://ghorbany.com/inspiration/collectors-alfred-cassirer/35078576_10216363847710938_3355713782939648000_o.jpg/@@images/648b6ebd-e9ea-4c90-b9eb-8670ce5541ce.jpeg)