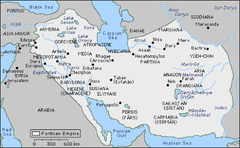

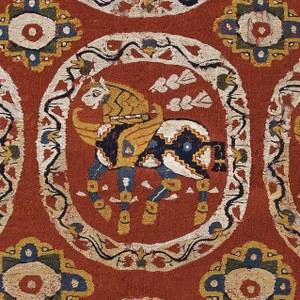

After the fall of the Sasanid Empire it would take 850 years before Iran came into Persian hands again, with the ascend of the Safavid Dynasty. The Safavids ruled from 1501 to 1722 and, at their height, they controlled all of what is now Iran, Azerbaijan Republic, Bahrain, Armenia, eastern Georgia, parts of the North Caucasus, Iraq, Kuwait, and Afghanistan, as well as parts of Turkey, Syria, Pakistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. Despite their demise in 1722, the legacy that they left behind was the revival of Iran as an economic stronghold between East and West, the establishment of an efficient state and bureaucracy, their architectural innovations and their patronage for fine arts. The Safavids have also left their mark down to the present era by spreading Twelver Islam in Iran, as well as major parts of the Caucasus, Anatolia, and Mesopotamia.

The history of the rise of the Safavid Order to political power is a long and interesting one. Persia was invaded and ruled by various Islamic and Monghol Dynasties after the fall of the Sasanid Dynasty, and the biggest change that occurred during this time was the conversion of Persians to Islam. Various Sunni factions and mystic orders arose inside Persia and one of them was the Safavid Order. Its founder was Safi-ad-din Ardabili, a Sufi mystic (1252 - 1334) who assumed the leadership of the Zahediyeh, a significant Sufi order in Gilan, from his spiritual master and father-in-law Zahed Gilani. Due to the great spiritual charisma of Safi al-Din, the order was later known as the Safaviyya. Much about the early Safavid Order remains unclear. One point of uncertainty is the precise nature of their religious beliefs. Originally, they seem to have harbored Sunni convictions, but under Ḵᵛāja ʿAli they are said to have gravitated toward Shiʿism under the influence of their main supporters—Turkmen tribes who adhered to a popular brand of Shiʿism. After the death of Safi-ad-din Ardabili the leadership of the Safavid Order passed through his descendants, always retaining its spiritual objectives, but in 1447 Sheikh Junayd assumed the leadership and he had material power aspirations. The Safavid Order had become a very powerful spiritual influence in the region, but the two most powerful and opposing tribal dynasties that held the material power were: the Qara Qoyunlu ("Black Sheep) and the Aq Qoyunlu ("White Sheep"). The leader of the Qara Qoynlu, Jahan Shah, realized that Sheikh Junayd had plans to take over power in his region and to avoid instability and destruction, ordered him to leave. Sheikh Junayd sought refuge with the opposition, the Aq Qoyunlu ruled by Khan Uzun Hassan. He cemented the relationship by marrying the Khan's sister and from that assured position started building up his position of power. He had his eye on the Shirvan region (Azerbaijan) but was killed after an incursion. His son Haydar Safavi assumed leadership of the Safavid Order and married Uzun Hassan's daughter, Martha 'Alamshah Begom, who gave birth to Ismail I, founder of the Safavid dynasty. After Uzun Hassan's death, his son and successor, Ya'qub, felt increasingly threatened by the Safavid influence in his tribe and decided to align himself with the Shirvanshah and killed Haydar in 1488. By this time, the bulk of the Safaviyya were nomadic Oghuz Turkic-speaking clans from Asia Minor and Azerbaijan and were known as Qizilbash "Red Heads" because of their distinct red headgear. The Qizilbash were warriors, spiritual followers of Haydar, and a source of the Safavid military and political power. After the death of Haydar, the Safaviyya gathered around his son Ali Mirza Safavi, who was also pursued and subsequently killed by Ya'qub. According to official Safavid history, before passing away, Ali had designated his younger brother Ismail as the spiritual leader of the Safaviyya. In order to avenge his father's and brother's deaths, Ismael invaded neighboring Shirvan in 1500 and in so doing, started the Safavid Dynasty.

Afterwards, Ismail went on a conquest campaign, capturing Tabriz in July 1501, where he enthroned himself the Shāh of Azerbaijan, proclaimed himself Shahanshah of Iran and minted coins in his name, proclaiming Shiʻism the official religion of his domain. The establishment of Shiʻism as the state religion led to various Sufi orders openly declaring their Shiʻi position, and others to promptly assume Shiʻism. Although Ismail I initially gained mastery over Azerbaijan alone, the Safavids ultimately won the struggle for power over all of Iran, which had been going on for nearly a century between various dynasties and political forces. A year after his victory in Tabriz, Ismāʻil claimed most of Iran as part of his territory, and within 10 years established a complete control over all of it. The expansionist policies of Ismail was highly disturbing for the powerful neighboring Ottoman Empire. The Ottomans, a Sunni dynasty, considered the active recruitment of Turkmen tribes (predominantly Shi'ite) of Anatolia for the Safavid cause as a major threat. To counter the rising Safavid power, in 1502, Sultan Bayezid II forcefully deported many Shiʻite Muslims from Anatolia to other parts of the Ottoman realm. In 1511, the Şahkulu rebellion was a widespread pro-Shia and pro-Safavid uprising directed against the Ottoman Empire from within the empire. The Ottomans led a large-scale incursion into Eastern Anatolia by Safavid ghazis under Nūr-ʿAlī Ḵalīfa. Even though they won major territory and the capital of Ismail, Tabriz, the Ottoman soldiers refused to spend the upcoming winter in the cold and the army returned back. This invasion was the first of a 200+ year long war fought between the Ottomans and the Persians that had major consequences for both sides.

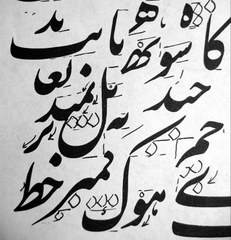

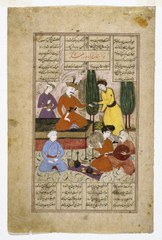

After the death of Shah Ismail, his young son, Shah Tahmāsp, took the throne. Iran was in a dire state, but in spite of a weak economy, a civil war and foreign wars on two fronts, Tahmāsp managed to retain his crown and maintain the territorial integrity of the empire (although much reduced from Ismail's time). During the first 30 years of his long reign, he was able to suppress the internal divisions by exerting control over a strengthened central military force. In the war against the Uzbeks he showed that the Safavids had become a gunpowder empire. His tactics in dealing with the Ottoman threat eventually allowed for a treaty which preserved peace for twenty years. In cultural matters, Tahmāsp presided the revival of the fine arts, which flourished under his patronage. Safavid culture is often admired for the large-scale city planning and architecture, achievements made during the reign of later shahs, but the art of Persian miniature, book-binding and calligraphy, in fact, never received as much attention as they did during his time. Another big change Tahmasp brought to the Safavid Dynasty was that of ruling classes. During his reign he had realized while both looking to his own empire and that of the neighboring Ottomans, that there were dangerous rivaling factions and internal family rivalries that were a threat to the heads of state. Not taken care of accordingly, these were a serious threat to the ruler, or worse, could bring the fall of the former or could lead to unnecessary court intrigues. For Tahmāsp the problem circled around the military tribal elite of the empire, the Qizilbash , who believed that physical proximity to and control of a member of the immediate Safavid family guaranteed spiritual advantages, political fortune, and material advancement. Despite that Tahmāsp could nullify potential issues related to his family by having his close direct male relatives such as his brothers and sons routinely transferred around to various governorship in the empire, he understood and realized that any long-term solutions would mainly involve minimizing the political and military presence of the Qizilbash as a whole. To solve this dilemma Shah Tahmāsp started the first of a series of invasions of the Caucasus region, both meant as a training and drilling for his soldiers, as well as mainly bringing back massive numbers of Christian Circassian and Georgian captives, who would form the basis of a military slave system (a system introduced by the Abbasid Caliphate during the reign of al-Mu'tasim (r. 833–842)), as well as at the same time forming a new layer in Iranian society composed of ethnic Caucasians. This was the starting point for the corps of the royal slaves, who would dominate the Safavid military for most of the empire's length. As non-Turkeman converts to Islam, these Circassian and Georgian soldiers were completely unrestrained by clan loyalties and kinship obligations. Many of the transplanted women became wives and concubines of Tahmāsp, and the Safavid harem emerged as a competitive, and sometimes lethal, arena of ethnic politics as cliques of Turkmen, Circassian, and Georgian women and courtiers vied with each other for the shah’s attention. After Tahmasp's death a 12 year period of political turmoil reigned between his sons and successors, until Shah Abbas took over in 1588.

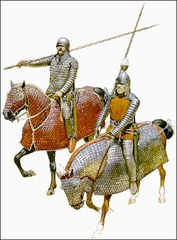

At only 16 years of age, Shah Abbas had to navigate his way and empire whilst solely relying on the support of the Qizilbash, yet over the course of ten years Abbas was able, using cautiously-timed but nonetheless decisive steps, to affect a profound transformation of Safavid administration and military, throw back the foreign invaders, and preside over a flourishing of Persian art. Abbas was able to begin gradually transforming the empire from a tribal confederation to a modern imperial government by transferring provinces from mamalik (provincial) rule governed by a Qizilbash chief and the revenue of which mostly supported local Qizilbash administration and forces to khass (central) rule presided over by a court appointee and the revenue of which reverted to the court. Particularly important in this regard were the Gilan and Mazandaran provinces, which produced Iran's single most important export; silk. With the substantial new revenue, Abbas was able to build up a central, standing army, loyal only to him. This freed him of his dependence on Qizilbash warriors loyal to local tribal chiefs.

What effectively fully severed Abbas's dependence on the Qizilbash, however, was how he constituted this new army. In order not to favor one Turkic tribe over another and to avoid inflaming the Turk-Persian enmity, he recruited his army from the "third force", a policy that had been implemented in its baby-steps since the reign of Tahmasp I—the Circassian, Georgian and to a lesser extent Armenian ghulāms who (after conversion to Islam) were trained for the military or some branch of the civil or military administration. The standing army created by Abbas consisted of 10,000–15,000 cavalry ghulām regiments solely composed of ethnic Caucasians, armed with muskets in addition to the usual weapons (then the largest cavalry in the world); a corps of musketeers, mainly Iranians, originally foot soldiers but eventually mounted, and a corps of artillerymen. Both corps of musketeers and artillerymen totaled 12,000 men. In addition the shah's personal bodyguard, made up exclusively of Caucasian ghulāms, was dramatically increased to 3,000. This force of well-trained Caucasian ghulams under Abbas amounted to a total of near 40,000 soldiers paid for and beholden to the Shah. Abbas also greatly increased the number of cannons at his disposal, permitting him to field 500 in a single battle. Ruthless discipline was enforced and looting was severely punished. Abbas also moved the capital to Isfahan, deeper into central Iran. From this time the state began to take on a more Persian character. The Safavids ultimately succeeded in establishing a new Persian national monarchy.

Even though Shah Abbas signed treaties with some Christian European empires against their common enemy, the Ottomans, it was ultimately his relationship with the English that proved most fruitful. Abbas was able to draw on military advice from a number of European envoys, particularly from the English adventurers Sir Anthony Shirley and his brother Robert Shirley, who arrived in 1598 as envoys from the Earl of Essex on an unofficial mission to induce Iran into an anti-Ottoman alliance. The Shirley brothers helped reorganize the Iranian army, which proved to be crucial in the Ottoman–Safavid War (1603–18), which resulted in Ottoman defeats in all stages of the war and the first clear pitched Safavid victory of their arch-rival. The English at sea, represented by the English East India Company, also began to take an interest in Iran, and in 1622 four of its ships helped Abbas retake Hormuz from the Portuguese in the Capture of Ormuz (1622). This was the beginning of the East India Company's long-running interest in Iran.

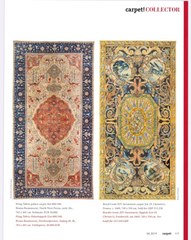

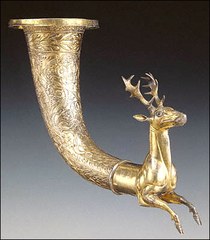

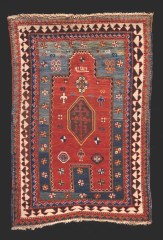

The growth of Safavid economy was fueled by the stability which allowed the agriculture to thrive, as well as trade, due to Iran's position between the burgeoning civilizations of Europe to its west and India and Islamic Central Asia to its east and north. The Silk Road which led through northern Iran was revived in the 16th century. Abbas I also supported direct trade with Europe, particularly England and The Netherlands which sought Persian carpet, silk and textiles. Other exports were horses, goat hair, pearls and an inedible bitter almond hadam-talka used as a spice in India. The main imports were spice, textiles (woolens from Europe, cottons from Gujarat), metals, coffee, and sugar. In the late 17th century, Safavid Iran had higher living standards than in Europe. According to traveler Jean Chardin, for example, farmers in Iran had higher living standards than farmers in the most fertile European countries.

Under the governance of the strong shahs, especially during the first half of the 17th century, traveling through Iran was easy because of good roads and the caravansaries, that were strategically placed along the route. Thévenot and Tavernier commented that the Iranian caravansaries were better built and cleaner than their Turkish counterparts. According to Chardin, they were also more abundant than in the Mughal or Ottoman Empires, where they were less frequent but larger. Caravansaries were designed especially to benefit poorer travelers, as they could stay there for as long as they wished, without payment for lodging. During the reign of Shah Abbas I, as he tried to upgrade the Silk route to improve the commercial prosperity of the Empire, an abundance of caravanseries, bridges, bazaars and roads were built, and this strategy was followed by wealthy merchants who also profited from the increase in trade. To uphold the standard, another source of revenue was needed, and road toll, that were collected by guards (rah-dars), were stationed along the trading routes. They in turn provided for the safety of the travelers, and both Thevenot and Tavernier stressed the safety of traveling in 17th century Iran, and the courtesy and refinement of the policing guards.

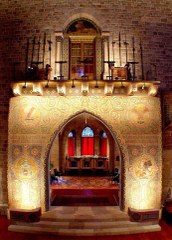

A new age in Iranian architecture began with the rise of the Safavid dynasty. Economically robust and politically stable, this period saw a flourishing growth of theological sciences. Traditional architecture evolved in its patterns and methods leaving its impact on the architecture of the following periods. Indeed, one of the greatest legacies of the Safavids is the architecture. In 1598, when Shah Abbas decided to move the capital of his Iranian empire from the north-western city of Qazvin to the central city of Isfahan, he initiated what would become one of the greatest programs in Iranian history; the complete remaking of the city. The Chief architect of this colossal task of urban planning was Sheikh Bahai , who focused the program on two key features of Shah Abbas's master plan: the Chahar Bagh avenue, flanked on either side by all the prominent institutions of the city, such as the residence of all foreign dignitaries. And the Naqsh-e Jahan Square ("Examplar of the World"). The ingenuity of the square was that, by building it, Shah Abbas would gather the three main components of power in Iran in his own backyard; the power of the clergy, represented by the Masjed-e Shah, the power of the merchants, represented by the Imperial Bazaar, and of course, the power of the Shah himself, residing in the Ali Qapu Palace. Distinctive monuments like the Sheikh Lotfallah (1618), Hasht Behesht (Eight Paradise Palace) (1469) and the Chahar Bagh School (1714) appeared in Isfahan and other cities. This extensive development of architecture was rooted in Persian culture and took form in the design of schools, baths, houses, caravanserai and other urban spaces such as bazaars and squares.

The demise of the Safavid Dynasty was caused by the ongoing threat of external forces such as the Ottomans, the Uzurks and the new rising Russian Muscovy; as well as internal upheaval by various tribes unhappy with the forced mass resettling of Qizilbash Turkic tribes in Khakheti to repopulate the province. The overseas trade routes run by European powers also hampered trade although Persia managed to maintain and grow the Silk Route over land. The Dutch and English continuously drained the Persian government from precious metals and thus took much needed funds out of the country. Bad management and reckless spending by the rulers following Shah Abbas II eventually led to Persia not being able to defend her borders and opened the way for the Hotak Dynasty, of Afghan Pashtuni descent, to take over power for a short period of time. Thanks to the bravery of the founder of the Afsharid dynasty, Nader Shah Afshar, the Hotaks were defeated in 1738 and he started the reestablishment of Iranian suzerainty over all regions lost decades before against the Iranian arch-rival, the Ottoman Empire, and the Russian Empire.