Some prayer rugs showcase the actual architecture of the mihrab in specific mosques whereas others are more abstract representations of the idea. The niche on a prayer rug is generally the place where the head is placed and the two spaces next to it, the place where you place your hands when kneeling down in prayer. This allows the participant to visualize the mihrab and in so doing also the Kaaba in Mecca and heaven. Prayer rugs are exclusively woven and used by Sunni Muslims. Muslims practising Shi’ite Islam, like majority Iranians, use prayer stones and their closest representation to a prayer rug would be those with the tree of life design.

What a shock then when some Shi’ite prayer rugs were discovered in the Topkapi Palace treasury. The carpet world came to a standstill. This was an impossibility! The speculation is that at the time that the balance of power fell to the Ottomans during Iran’s Safavid Dynasty, "the Safavid Shah Tahmasp, who reigned for 52 years during this regional warfare, turned to a policy of appeasement instead." He offered gifts to the Ottomans in many forms including carpets. Now it could be that he ordered prayer rugs to be woven in acknowledgement of the practices of the Ottomans, but including Shi’ite prayer inscriptions were either a diplomatic slap to the Ottoman faces or a way to introduce Shi’ite Islam to the predominantly Sunni Ottomans. Whatever the reason, these were the first and last Shi’ite prayer rugs woven as far as is known.

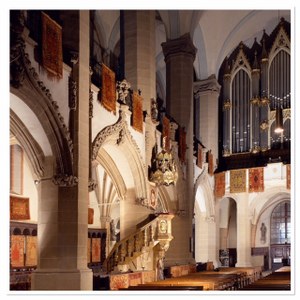

Another shock went through the carpet world when over 400 well preserved Ottoman prayer rugs were discovered in the Gothic Christian churches of Transylvania. How did this happen? What were prayer rugs, exclusively associated with Islam, doing in Christian churches? During the reign of the Ottomans the empire stretched as far as Austria, but not all countries were incorporated into the empire. Some previous Roman satraps remained independent but had to pay tribute to the Ottoman Empire. One such area was Transylvania that remained Christian.

“Organized trade between the Romanian countries and the Ottoman Empire began with Sultan Mehmed II's decree of 1456, granting Moldavian merchants the right to travel to Constantinople for trade. The role of Turkish rugs as trade goods of high value and prestigious collectibles is documented in the merchant accreditations, vigesimal accounts, municipal and church annals as well as individual contracts and wills, archived in the Transylvanian towns. The municipalities and other institutions of the Saxon towns, persons of nobility and public influence, as well as citizens were owners of Ottoman rugs. The towns acquired Turkish rugs either as customs duty paid in like, or purchased rugs from the trade. Rugs were frequently offered to public persons as a gift of honour.

Rugs were used to mark the place of individual persons, or members of a guild, in church. There is also evidence of collections owned by private persons. Contracts specify that the rugs were hung on the walls of private homes for decoration. As such, rugs were used to confirm the social status of the owner, but the reports also confirm that the carpets were perceived as objects of beauty and art. The Transylvanian Saxons referred to them as "Kirchenteppiche" ("church carpets") even though a significant number of the rugs which still are on display in Transylvanian churches show Islamic prayer rug designs.” These prayer rugs are still on display in the Transylvanian churches to this day.

There are mainly four types of prayer rugs identified in the churches: prayer rugs, single niche, double niche and column rugs. The prayer rugs display a single niche but with an empty field in a single colour in the middle field. The single niche has some decorative patterns inside the middle field. The Column rugs are characterized by column motifs supporting an architectural structure, most often an arch. “The Double-niche layout came into being probably because of the edict sent to Kütahya in 1610, under the rule of Sultan Ahmed I, which stated:

We heard that, weavers are producing carpets and seccades in your kazas (townships) depicting mihrab, kabe (Kaaba) and hat (calligraphy) on carpets and seccades and selling them to non-Muslims. Shaykh al-Islam prescribes this is against Islam and forbidden by şeriat.

(Ahmet Refik, Istanbul Hayati (1000 – 1100), Istanbul, doc. 83, pp.43-44 Transl. by Levent Boz, Ankara)

So, producing rugs for export in this format was a way of ostensibly obeying the Edict. When the second niche was added the field pattern had to be adapted. The idea of the double-niche could have been borrowed from small-medallion Ushaks or from book-binding but all the design elements reflect the Single-niche rugs.”

There are some examples of Christian “prayer rugs” too. The central shield-like design in Kazak Sevan rugs is thought by some to relate to the floor plan of Armenian churches. Interestingly the design also represents the Armenian grave stones that are made from a special soil. Historically when the demand in the west for prayer rugs increased a lot of Armenian workshops started producing them since they were also involved in dyeing the wool for these rugs before. This rug establishes the fact that some classic Caucasian designs were woven by Armenians, and it confirms the impression that Armenian rugs were part of the mainstream rug production in the nineteenth century rather than the periphery. There are many rugs woven by Armenians inside and outside of Iran, that include many Christian symbols in the design of their rugs.

Sources:

- http://tea-and-carpets.blogspot.co.za/2010/01/salting-carpets-and-topkapi-prayer-rugs.html

- http://www.armeniafest.com/carpet-weaving.html

- http://www.transylvanianrugs.com/?p=2425

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transylvanian_rugs