by Annette Ittig This was the winning entry in the ORR Essay Competition. Annette Ittig obtained her Ph. D. at the Oriental Institute, Oxford University, where she has studied under Mae Beattie. Her thesis topic is:

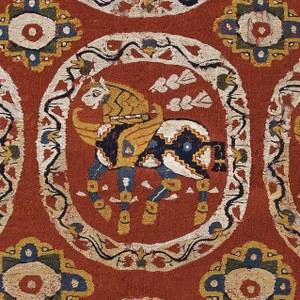

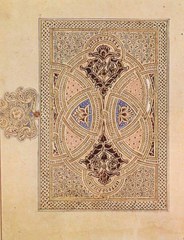

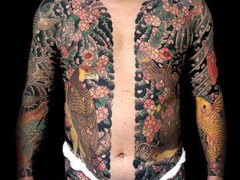

THE PERSIAN CARPET

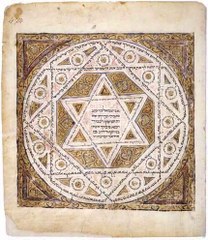

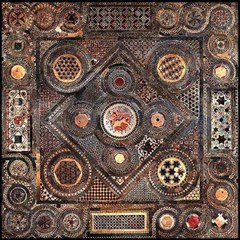

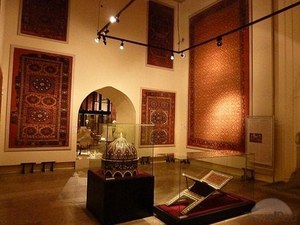

Even a brief glance at one of the bibliographies of Oriental carpet literature demonstrates that the Middle Eastern rug producing world consists of an intricate mosaic of geographical regions populated by diverse linguistic, ethnic and religious groups. It is therefore not surprising to find tremendous variations in the designs, palettes and structures among the rugs woven in Turkey, Persia, the Caucasus, India and Egypt. A review of the vast literature of each of these types of rugs is beyond the scope of this essay. Instead, this article focuses upon previous studies

and other sources relevant to the Persian carpet. The writer's previous fieldwork and researches, particularly a familiarity with the primary and secondary sources for

Persia, determined this choice.

Previous Studies: The Classical Persian Carpet

The scope and number of works published hitherto is clearly indicated by Enay and Azadi's Einhundert Jahre Orientteppich-Literatur, (Hannover, 1977), the most

comprehensive carpet bibliography. Within this extensive literature are two broad categories:

a) works concerned with rugs produced during the Safavid era and

b) publications dealing with later carpets. These will be dealt with in turn.

The works concerned with Safavid carpets are primarily art historical studies which analyze designs. They have established the criteria by which all other Persian rugs

have been judged, and have strongly influenced the attitude of scholars towards later Persian weaving. Scholars agree that Julius Lessing's Orientalische

Teppichmuster nach Bildern and Originalen des XV bis XVI Jahrhunderts (Berlin, 1877)1 initiated art historical research about the Oriental carpet. Through presentation of carpet patterns in mediaeval European paintings, Lessing aimed to provide the designers of modern carpets with "classical" models (2). He maintained that the finest carpet designs, an "Idealtypus", were produced during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, and that they deteriorated thereafter (3). Later art historical literature has assessed Persian carpets by these same criteria.

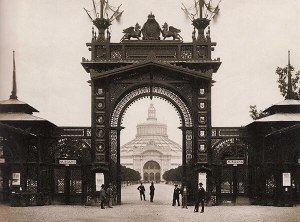

The 1891 Vienna Exhibition, which was the first international show devoted to carpets, invalidated Lessing's assumption that very few very old carpets had

survived. Of the 515 pieces exhibited in Vienna; many were antique. The three volumes resulting from this exhibition (4) contain superb plates and excellent articles

about carpet manufacture at that time. For example, the article by Churchill, a British diplomat interested in commerce, is informative about the organization of the

contemporary Persian carpet industry, including the materials and personnel employed. There is also an Exhibition handbook (5) which lists the prices of exhibits

from commercial houses. It thus provides an index of contemporary taste and investment patterns. The exhibits and articles illustrate the organizers recognition of

a need for co-operation between academia and the trade in the study of carpets. It is regrettable that later authors have largely ignored this approach.

At the time of the exhibition, the organizers also requested F. R. Martin to produce a history of the Oriental carpet. Martin's text, A History of Oriental Carpets Before

1800 (Vienna, 1908) was not published until some seventeen years later, after he had undertaken extensive fieldwork in the Middle East. Martin's dating and

provenance of Persian carpets were based not only on comparative designs in other Persian media and European paintings, because of his field experience, he

also utilized information about antique and contemporary carpets from the trade. His attribution of the "vase" rugs to Kirman on the basis of both textual evidence and the

similarity of their weave to that of modern Kirmani Carpets (6) is upheld by recent scholarship. Because of his consideration of carpet weaves as a factor in determining provenance, Martin also illustrated the backs of some antique pieces (7).

Another important work on early carpets was Wilhelm von Bode's Vorderasiatische K & uumlpfteppiche aus alterer Zeit (Leipzig, 1901). This book was subsequently

revised with K & Umlhnel and later translated into English by Ellis (8). Bode and K &Umlhnel were mainly concerned with design as an indication of provenance. They based part of their chronology for Persian rugs upon comparative examples in European paintings. However, their dating based upon designs in Persian miniature paintings is questionable, as none of these exactly correspond to any extant carpets. Moreover their assertion that "The golden age of the (classical) class doubtless falls within the first half of the sixteenth century (9) is unproven: only two

dated pieces support their case.

The section on "The Art of Carpet Making" in A. U. Pope's A Survey of Persian Art (New York, 1938-39) is still the most comprehensive work on pre-nineteenth century

Persian carpets. In this section, Jacoby's article on "Materials used in the Making of Carpets" (pp. 2456-65) gives an adequate description of the types of wool and

dyestuffs traditionally employed. Mankowski's article, "Some Documents from Polish Sources Relating to Carpet Making in the Time of Shah Abbas I" (pp. 2431-36)

provides the first documentary evidence for the attribution of certain "Polonaise" carpets to Kashan.

In his article on "The History of Carpet Making", Pope classifies surviving carpets into groups according to their design, and attributes these groups to particular centres of manufacture. He defines the four major centres of Safavid production as Tabriz or northwest Persia; Herat or northeast Persia; Kirman or southeast Persia; and central Persia. His attributions are sometimes questionable. For example, despite the evidence presented by Mankowski and several European travellers to Safavid Persia regarding the weaving of "Polonaise" carpets in Isfahan and Kashan; Pope attributes the majority of the Polonaise rugs to Joshagan (10). Pope's opinion was based on oral tradition related to him by local residents and upon the nisba of the weaver of the Qum shrine fragments (11).

His rejection of reliable European sources in favor of hearsay and a nisba which merely indicates that the Ustad Ni'matulla, or his family, was from Joshagan, seems

unreasonable.

Pope's use of nisba was in any case inconsistent. He rejected the Kirmani signature on a vase rug and the Mahani nisba on the Sarajevo fragments as evidence for

their having been produced in the Kirman region. Rather, he attributed these rugs to Joshagan (12), again on the basis of oral tradition. Almost all later writers have

rejected Pope's contention that Joshagan produced most of the surviving Polonaise and vase rugs as inadequate. More recent scholarship has followed Mankowski's

attribution for an Isfahan or Kashan provenance for the former and Martin's Kirman attribution for the latter (13).

While many of Pope's local attributions indicate a superficial scholarship, the achievements of the "Carpet" section of the Survey are undeniable. The scope of

the work is enormous with 153 carpets represented. Some of these pieces, such as the fragments from the Qum shrine and the Sarajevo carpet, had not previously

been published. Moreover, Pope recognized the need for structural analysis to supplement design for provenance (14). His illustrations of carpet structures demonstrated that many "classical" carpets have similar weaves (15).

In his review of the Survey "The Art of Carpet Making (16) as well as in his book Oriental Carpets: An Account of Their History (17) Erdmann generally concurred

with Pope regarding places of manufacture. However, Erdmann followed Martin in suggesting a Kirman provenance for the "vase" carpets (18). He also cited Kashan as the location of manufacture for the Sangusko carpets19 as opposed to Pope's attribution of Kirman or Yazd. Erdmann's researches into the Oriental carpet

focused primarily on Turkish material. It is therefore not surprising that one of his greatest contributions to Persian Carpet studies was the identification of the so-called Salting pieces as later Turkish rugs (20). Indeed, his was one of the first works to discuss the problem of artful, modern reproductions of "classical" carpets. Erdmann based his provenance of Persian rugs primarily upon comparative design analyses. Moreover, he adhered to the earlier art historical concept of the "Idealtypus" of classical carpet design, and he therefore viewed any deviation from

this "court" style as indicative of later manufacture (21). His failure to recognise that several types of carpet weaving existed in Persia analogous to those he saw in Turkey, e.g., nomadic, cottage, and urban as well as court production, can be best explained by his lack of fieldwork in Iran.

In Seven Hundred Years of Oriental Carpets (22) Erdmann briefly extended his comments about classical Persian rugs to include eighteenth and nineteenth century pieces. An indication of his superficial treatment of the latter is his statement that dated Persian carpets always contain the signature of the weaver (23), moreover his discussion of the alteration of dates in carpets is adjacent to the

illustration of a rug whose forged date he accepted (24).

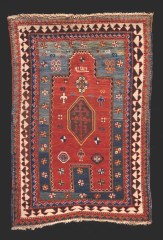

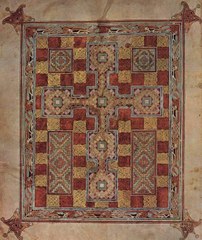

The first publication to rigorously base the classification of classical Persian carpets upon structure was Beattie's catalogue of the exhibition Carpets of Central Persia

(Sheffield, 1976). Many of the carpets exhibited had vase motifs in their fields. The type of weave common to most of the rugs on display was accordingly defined by

Beattie as "vase technique". She then arranged the vase-technique rugs in subgroups according to their designs.

Beattie does not attribute the vase-technique rugs to any particular centre. However, she does include a nineteenth century Kirman Carpet (25) because of its structural similarity to the other entries. She thus appears to agree with Martin's statement about Kirman as a place of manufacture for at least some of the vase-technique rugs.

Beattie's stress on structure as an indication of provenance has encouraged recent carpet studies to emphasize technique; and descriptions of structure, colour and dyes are now often noted. There is, however, some controversy about the manner in which technical information should be presented.

In summary, not only has the literature on classical Persian carpets advanced little from the turn of the century until Beattie's publication on vase -technique, but it has

consistently considered the Persian carpet from a purely Western perspective. In other words, scholars have judged the Persian carpet in the same way as European

art: by the standard of court, and in the European context, church products. This approach to Persian carpets is questionable on several counts. Firstly, no pieces

known to me had been specifically ordered by the Safavid court. Secondly, there is no well-defined chronology of Safavid carpets. With the exception of five dated

pieces (26); we are unable to place or date any carpets with any certainty. Thirdly, little attention has been paid to the substantial body of Persian sources such as

court histories, administrative manuals, decrees and shrine inventories for information about the organization of workshops: specific commissions and donations; or the trade in carpet materials. For example, both Persian and

European sources indicate that in Safavid times, there were both specially commissioned carpets and rugs woven for a mass market. Moreover, a court workshop was permitted to undertake outside commissions (27). Noting the high quality of carpets woven in some provincial centres in the nineteenth century (28), it is possible that many extant classical Persian rugs were not court commissions. Fourthly, the theory that designs filtered from court workshops into other urban and non-urban products in degenerate forms disregards the interdependence of the

urban and non-urban sectors of Persian society. Hence, court carpets may arguably represent refined descendants of non-urban folk weaving.

Previous Studies: The Modern Persian Carpet

Most of the publications about modern Persian carpets are essentially "buyer's guides". Generally written by dealers, such books usually consider rugs as either investments and/or furnishings. As a result, nomenclature often refers to a rug's quality, or the market in which it was purchased, rather than to design. The first publication of this type was J. K. Mumford's Oriental Rugs (New York, 1900). Because it emphasizes rugs on the market, this work referred to carpets by their trade names (29). In a table, Mumford listed those Oriental rugs most commonly seen on the Western market, with their technical characteristics (30)

Some of this technical information is incorrect. Indeed, Mumford is partially responsible for some of the misinformation concerning the origins and uses of

oriental rugs later perpetuated in trade publications. However, Mumford's book was a pioneering effort. It was the first work to devote itself essentially to contemporary

rugs and their classification according to both design and weave.

Apart from Mumford, two other significant buyers' guides should be noted. A. U. Dilley's Oriental Rugs and Carpets (New York, 1931) was one of the earliest works to describe the ways in which Western market demand affected the design and quality of the modern Persian carpet. On the basis of trade sources, he concluded that the bulk of carpet weaving in Persia at that time was produced for export to the West.

Chandler Robbins Clifford's Oriental Rugs (New York. 1911) was the first publication on modern rug's to illustrate specific local weave patterns with photographs of their

backs. A more recent attempt to identify modern rugs on the basis of their weave patterns is Neff and Magg's Dictionary of Oriental Rugs (31). The colour plates in

this publication more clearly illustrate weave than Clifford's black and white photographs. The Dictionary's material is also more coherently organized. However, the authors are clearly indebted to the works of Clifford and other earlier writers for their historical background.

The only book to place contemporary Persian rugs in the context of the modern industry is A. C. Edwards' The Persian Carpet (London. 1953). Edwards was the

manager of the Oriental Carpet Manufacturer's operations in Persia from 1908 to 1924. His first hand observations about the designs, craftsmen, and weaves of the

various rug manufacturing regions in Persia are thus particularly valuable. Edwards' book also demonstrates the great extent to which foreign capital was involved in

Persia's rug industry in the early twentieth century. The Persian Carpet is, moreover, the first rug book to name the Azerbaijani entrepreneurs who organized an export industry prior to OCM's. Sadly, as The Persian Carpet was written for a general audience, it does not give specific details about OCM itself, the "second generation" (after Ziegler's) of Western involvement in the Persian carpet industry. Apart from buyers' guides, other publications about modern Persian weavings include exhibition catalogues. Bierman and Bacharach's The Warp and Weft of Islam (Seattle, 1978) is particularly relevant. Here, Bierman discusses the fashion

for Oriental carpets in America at the turn of the century, and she presents evidence from the trade about sizes and colours demanded by that market. Using this historical information with technical and stylistic analysis, Bierman and Bacharach are able to identify certain Persian rugs made for American clientele. Thus, The Warp and Weft of Islam, is one of the few recent publications to utilize

information from both art historians and dealers.

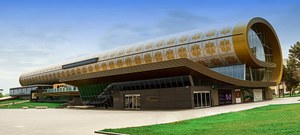

Another important catalogue is Azadi's Farsh-i Iran/Persian Carpets (32) with its illustrations and technical analyses of forty carpets in the Carpet Museum of Iran. Most of these pieces were originally in the Gulistan Palace and were either presented to or commissioned by members of the Qajar and Pahlavi dynasties. They are thus invaluable primary documents for the study of later Persian carpets.

Azadi had prefaced the catalogue with a brief discussion of past studies of the Persian carpet. In this, he particularly disagrees with the emphasis by art historians on Safavid carpets which, he points out, has hindered research into later rugs. The quality of the colour plates and the technical diagrams in the catalogue are superb. However, the English translation included in the text is awkward, and Azadi's comments on design are unfortunately omitted from it.33 Another significant Persian catalogue is Sirus Parham's Namayishgah-yi Qali-yi Kirman (n.p., 1978) in which cartoons are illustrated. Parham's dating for them is based principally upon the styles demanded by Western firms between circa 1901 and 1950. Unfortunately,

none of them are signed or dated. The English summary of the Persian text omits several interesting details -- mention of the master designers' names and the existence of the naqshkhauni "design caller". Parham's work demonstrates the importance of local sources and artifacts in the study of later Persian carpet manufacture. It thus suggests a guideline for future fieldwork, when that is again possible.

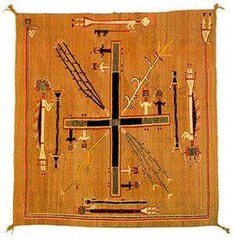

Some of the more recent publications consider modern Persian rugs from perspectives other than those of the art historian or dealer. A comprehensive and well-illustrated example of an interdisciplinary approach is Housego's Tribal Rugs (London, 1978). Her book, which is based upon fieldwork over several years, combines historical, art historical and ethnographic perspectives. It describes

contemporary non-urban weaving and weaving techniques by region and demonstrates that technically complex, attractive carpets continue to be produced in non-commercial situations.

Another important publication which has taken an ethnographic approach to its subject is The Qashqa'i of Iran (34). This work examines textile crafts within the

context of tribal life. From their first hand observations, the compilers describe contemporary dye stuffs, dye and fibre preparation, weaving implements and techniques, and the uses of textiles, data not normally available through a more

traditional art historical approach. This type of information demonstrates the vitality of contemporary weaving and gives greater meaning to the objects.

A primarily technical approach to contemporary carpets is taken in The Traditional Crafts of Persia (35) by H. E. Wulff, who was the principal of the Technical College

in Shiraz between 1937 and 1941. In his section on "Textile Crafts", Wulff discusses carpet weaving as well as the development of textile techniques, preparation of

fibres, dyes and looms. He provides evidence from archaeological, historical and literary sources to support his first hand observations. Moreover, he includes Persian terms for materials and techniques. Wulff clearly illustrates his discussion of carpet techniques and structures with diagrams and black and white plates. With his knowledge of Persian and his keen observation of materials, Wulff demolishes some traditional trade terminology: for example, he shows that the term shuturi refers not

to camel wool, but to camel-coloured wool (36). His comprehensive bibliography notes, historical, literary, archaeological, technological and anthropological works

relevant to the study of both antique and modern carpets.

The publications of Whiting (37) demonstrate another type of technical approach to later Persian rugs. Whiting, an organic chemist, is interested in dye analyses for their indications of carpet dating and provenance. Certainly the presence of synthetic dyestuffs indicates 1854 as the terminus post quem for manufacture. However, the relevance of dye analyses to provenance of later Persian rugs is somewhat questionable. In view of the scale of inter-provincial trade in dyestuffs in Qajar Persia, one of the most interesting results of Whiting's meticulous work is the documentation of the wide variety of vegetable materials used in the production of Persian carpet dyes.

A regional approach to the modern Persian carpet is seen in Bazin's Le travail du tapis dans la region de Qum.38 As a geographer Bazin is concerned with the symbiotic relationship between the city and its surrounding villages in the carpet industry. His first hand observations provide valuable insights into the collection and distribution of orders, materials and carpets. These demonstrate the dominance of the city over the organization of finance, production and marketing of the region's rugs.

Future Directions: Archival and Historical Sources

Certain of the aforementioned approaches to study of the Persian carpet are now unfortunately curtailed due to the difficulties in undertaking fieldwork in Iran. However, considerable documentation about Persian carpets is to be found in the material collected in Iran by European and American government officials, merchants and travellers, much of which is available in Western governmental

archives such as those of the U. S. Department of State.

Many of the European consuls were appointed from the Western mercantile community in Persia. As appointees were permitted to combine their consular duties with their business activities, their observations are particularly valuable to the study of Persian foreign and domestic trade. Since these consuls were more concerned with Western commercial interests than Persian internal trade, most of their statistics relate to imports and exports. The major source of data on foreign trade utilized by consuls and businessmen was the Persian masters of the various customs houses, until the customs reform of 1900-01. Such figures are problematic, as there is no evidence, that they were derived from systematic registration of all the articles passing through any particular customs house. Nor were goods in transit through Persia generally differentiated. Moreover, noting the references to contraband trade in the sources, smuggling must have been, widespread. Thus, although they do not

provide useful indications of commercial trends, the custom house figures cannot be considered absolute.

The economic surveys by Blau (39) and Polak (40) also contain data on carpets as articles of trade. Polak, who was personal physician to Nasir al-Din Shah from 1855

to 1860, wrote a very detailed description of the handicrafts in Persia including Persian terms for various objects. The Burgess letters (41) also provide details on

Persia's import-export trade, particularly for woollen cloth imports and raw silk exports.

Accounts by other travellers supplement this economic information. In this respect, the works by Isabell Bird Bishop (42) and Ella Sykes are of particular interest. Both

were keen observers of Persian domestic life, the daily routine of which generally included carpet weaving. As women, both were permitted access to the women's

quarters, generally inaccessible to men outside the immediate family.

Secondary sources particularly relevant to study of the Persian carpet include the researches of Issawi (44) and Floor (45). Issawi's Economic History of Iran, which

presents excerpts from a variety of primary sources, concentrates on themes such as international trade and technological advances. As such, this work gives a well

organized introduction to a complex topic, and his extensive bibliography is a valuable source of reference. Issawi has relied heavily on Western sources for his

information. On the other hand, Floor's study of the merchants in Qajar Persia utilizes several local sources. The latter provide valuable information on the dynamics of local commerce.

In comparison with Western records, contemporary Persian sources provide little quantitative data about the carpet industry. They do, however, provide insight into

both the Qajar social hierarchy and local economies. There are extensive collections of nineteenth century court and local histories and travellers accounts in Western libraries such as the British Museum; the Bodelian; the New York Public Library; and the oriental libraries of Harvard and Princeton.

One example of an informative Persian traveller is Hajj Sayyah (46), the peripatetic landowner from Mahallat. His description of the miserable conditions under which

the weavers of Kirman worked, and their low wages, shows the darker side of the boom described by Western writers.

There may be relevant records in Iran which are not accessible at present. Material in the Gulistan relating to the Carpet Museum collection, or inventories in shrines

such as those at Qum or Mashad, would be invaluable in establishing provenance for carpets. The papers of merchants or notables involved in the carpet trade and

manufacture might also provide insights into the organization of the industry. In summary, there are numerous historical and archival sources, in both Persian

and Western languages which have not yet been extensively used in carpet studies and which are accessible without travel to Iran. Interestingly, most of these sources are based on first hand observations made in Iran. Such information is invaluable in

supplementing observations derived from examination of the carpets themselves. Archival research is generally considered the prerogative of academia, and "hands

on" knowledge of carpets that of the trade. It is hoped that this essay will encourage greater cooperation between these groups in future carpet studies.

FOOTNOTES:

1. The English version of Lessing's book is Ancient Carpet Patterns After Originals of the 15th and 16th Centuries, (London, 1879).

2. Lessing op. cit. p. 5: "These patterns form such very superior models for modern productions that the author has considered it eminently desirable to bring them into notice with that object in mind."

3. Lessing, p. 6.

4. C. Purdin-Clarke (ed.), Oriental Carpets (Vienna, 1897).

5. Austellung Orientalische Teppiche im K. Osterreiches Handels Museum, (Vienna, 1891). I am indebted to Mr. Jack Haldane for this reference.

6. F. R. Martin, A History of Oriental Carpets Before 1800 (Vienna, 1908). P. 76

7. Martin, op. cit., figs. 365-74.

8. W. von Bode and E. Kühnel, Antique Rugs from the Near East trans. C. G. Ellis (Berlin, 1958).

9. Bode-Kühnel, op. cit., p. 87.

l0. A. U. Pope. "History of Carpet Making", Survey of Persian Art. ed. A. U. Pope (New York; 1938-39) p. 2393

11. Ibid.

12. Survey, op. cit., pp. 2386-87.

l3. See, for example, Colloquium on the Car- pets of Central Persia (Sheffield, l976).

14. Survey, pp. 2444-46.

15. Survey, p. 2446 and fig. 801.

16. K. Erdmann, "Rezension, ‘The Art of Carpetmaking', in a Survey of Persian Art", Ars Islamica VIII (1941), pp. 121-91.

17. K. Erdmann, Oriental Carpets: An Account of Their History, trans. C. G. Ellis (London, 1960).

18. "Rezension", op. cit. p. 189.

19. "Rezension", p. 111.

20. "Rezension", p. 167.

21. Erdmann, Oriental Carpets, op. cit., p. 45: "Whatever survives or is reanimated in the course of the nineteenth century is but a remnant of the wealth that once

existed."

22. K. Erdmann, Seven Hundred Years of Oriental Carpets, trans. M. H. Beattie and H. Herzog (London, 1970).

23. Seven Hundred Years op. cit. p. 175.

24. Seven Hundred Years pp. 111-2. For a discussion of this rug, the correct date of which is 1309/1891-2 rather than 1209/1794, see A. Ittig. "A Group of Inscribed

Carpets from Persian Kurdistan", Hali, IV/2 (1981).

25. M. H. Beattie, Carpets of Central Persia (Sheffield, 1976), no. 59.

26 These are the Victoria and Albert and Los Angeles County Ardabil carpets dated 942\1535-6 (Survey, pls. 1134-6); the Poli- Pezzoli hunting carpet of 929/1522-3

(Survey, pl. 1118); the Sarajevo fragments dated 1066/1655-56, (Survey pl. 1238); and the Qum fragments dated 1082/1661-2, (Survey pls. 258-60).

27. J. Chardin, Voyages du Chevalier Chardin en Perse(Paris, 1811), vol. VII, pp. 329-34. 28. See Ittig, op. cit.

29. J. K. Mumford, Oriental Rugs (New York, 1900), p. 196.

30. Mumford, op. cit. p.268.

31. I. C. Neff and C. V. Maggs, Dictionary of Oriental Rugs (London, 1977).

32. S. Azadi, Farsh-i Iran/Persian Carpets. (Hamburg, 1978).

33. Azadi, op. cit. p. 19.

34. The Qashqa'i of Iran (exhibition catalogue), Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester University (Manchester, 1976).

35. H. E. Wulff, The Traditional Crafts of Persia (Cambridge, Mass., 1966).

36. Wulff, op. cit.

37. M. Whiting and J. Harvey, "An Analysis of Dyes in Rugs and Bagfaces from Fars", Woven Gardens, D. Black and C. Loveless (London, 1979)

38. M. Bazin, "Le Travail du Tapis dons la region du Qom", Bulletin de la Societe Lanquedoc cienne de Geographic, t. Vll (1973), pp. 83-92.

39. F. O. Blau, Commerzielle Zustande Persiens (Berlin, 1858).

40. J. E. Polak, Persien, das Land und seine Bewohner (Leipzig, 1865).

41. C. and E. Burgess, Letters from Persia, ed. B. Schwartz, (New York, 1942).

42. I. B. Bishop, Journeys in Persia and Kurdistan (London, 1891).

43. E. Sykes, Through Persia on a Sidesaddle (London, 1898).

44. C. Issawi, ed., The Economic History of Iran, 1800 - 1914 (Chicago, 1971).

45. W. Floor, "The Merchants (Tujjur) in Qajar Iran", Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenlandischen Gesellschaft, Bd. 126 (19?6).

46. Hajj Muhammad Ali Mahallati Sayyah, Khatirat-i Hajj Sayyah, ed. Hamid Sayyah

(Tehran, 1346/1968).